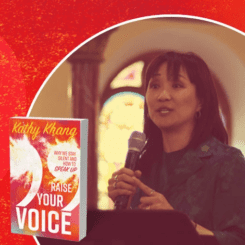

Kathy Khang is coming to Eastern University on Friday, September 27th!

Windows on the World: Kathy Khang

September 27, 10:00 AM

Eastern University | St. Davids Campus

“Raise Your Voice: Embodying the Body of Christ in Word and Deed”

Kathy Khang will interrogate the U.S. church’s silence around injustice, using the separation of church and state as an excuse, while taking advantage of tax deductions and exemptions to protect the financial well-being of institutions over the well-being of people. Kathy will draw from her recent book, Raise Your Voice: Why We Stay Silent and How to Speak, to examine the implications of staying silent, and the importance of raising our voices and using our influence to bring about the Kingdom of God on earth as it is in heaven.

If you’re in the area, we hope you can join us!

I first encountered Kathy Khang on social media several years ago. I don’t remember the specific issue she was addressing, but I remember reading her tweets and Facebook comments with a combination of admiration and awe. She challenged the status quo and spoke truth to power with confidence, clarity, and wit.

The former journalist and current InterVarsity staff worker have continued to speak up in this way since then: about Black Lives Matter, about Asian American stereotypes in media, about recent political attacks on immigrants, the undocumented, and refugees. I see Khang advocating for justice and equality consistently, courageously, and—in my mind—fearlessly.

In her new book, Raise Your Voice: Why We Stay Silent and How to Speak Up (IV Press), she peels back the curtain on her experience of joining such public square debates. Learning to use her voice has been far more difficult for Khang than her average Twitter follower might guess. She shares honestly and authentically about her journey of speaking out, including her fears and insecurities, the times she has been silenced by others, and the real costs of confronting the majority.

As a Korean American immigrant and a female leader in the evangelical world, Khang is well-positioned to provide insight into the challenges and risks of pushing back against systemic ignorance and injustice. “Outspoken women are often called aggressive, arrogant, or abrasive,” she writes. “… Women of color sit precariously and boldly at the intersection of race and gender, where raising our voices is a subversive, counter-cultural act that can earn us the labels of defiant or threatening: the angry Latina or black woman, the dragon lady, or even Pocahontas.”

As a Korean American immigrant and a female leader in the evangelical world, Khang is well positioned to provide insight into the challenges and risks of pushing back against systemic ignorance and injustice.

Yet there is no question in Khang’s mind that speaking up is imperative. When we do so, we honor the voice that God has given each of us, and we play a key role in advancing restoration and redemption in our churches and our communities. “The challenge to raise your voice is about doing the good work of the good news,” she explains early on. Later, she expands on this idea: “…our ability to influence—our voice—is never for individual gain and safety but is intended to steward creation and encourage the flourishing of one another in community and in relationship with God.”

Not speaking up, Khang argues, communicates something just as significant.

By temperament and family culture, Khang and I are very different. She confesses to being a quick thinker who can impulsively jump into the fray, using snark and sarcasm to fight back even when that may not be particularly effective.

I fit far more neatly into the Asian American stereotype. I prefer listening and observing over speaking out; I hate conflict and confrontation, especially with strangers online. Just thinking about entering a debate or challenging an authority figure gives me a stomachache. Even in my writing, I am reluctant to address political and theological issues that may ruffle feathers.

But Raise Your Voice creates space for everyone—and indeed honors the ways in which we are different. It is our uniqueness that makes our contributions to society, culture, and the church so crucial. We each have a story to tell that no one else can, and sharing that story benefits humanity as a whole. Speaking up begins, then, with knowing who we are and the distinct narrative we each have to tell.

Khang’s most encouraging words come when she is addressing readers like me, people who are uncertain, self-doubting, and more than a little scared about making our views known publicly. “I want you to know that you have a voice,” she says. “God wants you to use it, and the world needs to hear, see, and experience it.” She takes pains to list out the many ways our unique perspective can be expressed. You do not need to tweet regularly, let alone even use Twitter, to raise your voice. You can speak through art, through prayer, through financial giving, through your very presence.

But even the boldest among us can hesitate at times, wondering if we are the right people to speak up, when to do so, what to say, and how to do it.

This is where Khang’s deep dive into the story of Esther is especially helpful. She returns to this biblical narrative over and over throughout the book, exploring the oft-told story through a fresh and thought-provoking lens.

Like many people of color in the U.S., Esther must navigate between cultures and classes and power structures. She is a Jewish woman who is “passing” as a Persian queen, with her Persian name taking precedence over her given Hebrew name of Hadassah.

These circumstances complicate Esther’s sense of identity, which then makes it difficult for her to know her voice. In addition, her privilege as a member of the king’s household isolates her from what is happening in her community. When she first learns of her uncle Mordecai’s public grief in response to the execution order against the Jews, she worries more about how his sackcloth and ashes appear than why he is actually mourning.

Esther must undergo an extended process of introspection, of being challenged by Mordecai, of recognizing her power, and fasting and praying before God all prior to agreeing to advocate for her people. Only then can she step before the king and use her voice—even with the threat of death hanging over her.

Few of us are born knowing how to speak up and what to speak about. This is very much part of our spiritual journey, our personal transformation. And like any form of transformation, it does not happen alone. Khang reminds us that we need wise people around us who will call out our gifts and passions, who will coach and challenge us. We need the Holy Spirit to give us the courage and the words. We need God to remind us over and over again that even those with whom we fiercely disagree carry Imago Dei and should be treated with honor, dignity, and care.

Few of us are born knowing how to speak up and what to speak about. This is very much part of our spiritual journey, our personal transformation. And like any form of transformation, it does not happen alone.

This comes up several times in the practical lists of recommendations that Khang intersperses throughout the book. At multiple points, she emphasizes the importance of listening, asking questions, and approaching others with respect and humility. “…if we are genuinely interested in influencing others, raising awareness, and changing the hearts and minds of other people, we need to listen and ask questions,” she explains. “We need to understand how our message is being received and how people are hearing our voices.”

In this era, when anyone can fire off a knee-jerk social media post or comment in seconds, I wished for a longer meditation from Khang on these points. How do we see Imago Dei in someone when all we know is their social media handle? How do we slow down a heated debate enough to ask questions and listen? How do we communicate humility and respect when our written emails and comments can be so easily misunderstood?

The reality is that when we are speaking on issues that we care deeply about when we are clear about what is just and good when we feel like we are acting out of God’s calling, it is far too easy to go the way of anger, pride, and judgment. We can easily focus far more on winning the argument or outwitting an adversary than on the flourishing of everyone involved. This ongoing battle with the sin in our own hearts is both real and dangerous, and I, for one, know that I need more tools to fight these temptations.

Even without this, Raise Your Voice carries much wisdom, inspiration, and concrete advice for those who want to use their voices for reconciliation and justice, especially those whose voices are not heard from, acknowledged, or respected enough in the public square.

In these days of intense political division, online vitriol, and alternative facts, we desperately need these perspectives and stories to help us see the whole picture of God’s coming kingdom. For the sake of the gospel, we should each be willing to undergo the costly, yet ultimately redemptive process of sharing our voice with the world. And we should each seek out opportunities to call out this gift in others.

That’s what Khang does wonderfully in Raise Your Voice. She is both a mentor and advocate, challenging each of us to add our unique voices to the God-honoring chorus and speak up.

Dorcas Cheng-Tozun covers how startup life affects marriage, family, and personal well-being, based on more than 17 years of partnership with her entrepreneur-husband, Ned Tozun. She is the author of Start Love Repeat: How to Stay in Love with Your Entrepreneur in a Crazy Startup World, and her award-winning writing has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, the Unreasonable Institute, BlogHer, and dozens of other publications. Previously a nonprofit and social enterprise professional, she served as the first director of communication and human resources for d.light, one of the world’s leading social-benefit companies. A native of Silicon Valley, Dorcas has also lived and worked in China, Hong Kong, and Kenya.

covers how startup life affects marriage, family, and personal well-being, based on more than 17 years of partnership with her entrepreneur-husband, Ned Tozun. She is the author of Start Love Repeat: How to Stay in Love with Your Entrepreneur in a Crazy Startup World, and her award-winning writing has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, the Unreasonable Institute, BlogHer, and dozens of other publications. Previously a nonprofit and social enterprise professional, she served as the first director of communication and human resources for d.light, one of the world’s leading social-benefit companies. A native of Silicon Valley, Dorcas has also lived and worked in China, Hong Kong, and Kenya.