I don’t think it comes as a surprise to note that the record on justice is spotty at best for white evangelicals. It has not been part of our normative framework for thinking about the gospel and the mission of the church. Beyond that, justice issues often get framed as liberal, making it difficult to have nuanced conversations about modern-day injustice at the level of the local evangelical congregation.

…justice issues often get framed as “liberal,” making it difficult to have nuanced conversations about modern-day injustice at the level of the local evangelical congregation.

In the main, the history of evangelicalism in the United States is evidence of our leeriness if not outright opposition to the pursuit of justice. In 1947, Carl F. H. Henry, the first editor of Christianity Today, lamented this reality: “It remains a question whether one can be perpetually indifferent to the problems of social justice and international order, and develop a wholesome personal ethics.” Seventy years ago the problem of a disconnect between justice and the lived faithfulness of evangelicals in the United States was a most pressing concern. Sadly, not much has changed.

Our current reality is such that evangelical justice-seekers have largely become a sidelined people. Most evangelicals who have a passion to seek the shalom of God in the world have found that their local congregation is indifferent or antagonistic to that desire. In some rare cases, this congregational marginalization looks like an often-overlooked justice team, but that is probably an exception rather than the rule. The most likely scenario is that justice-minded evangelicals have learned that the local evangelical congregation is not a safe space to work out those passions.

It is not surprising, then, that this antagonism parallels the rise of evangelical parachurch organizations focused on issues of justice. Understandably these folks, feeling unwanted in local congregations, have increasingly gravitated toward the more proactive organizations and movements that have sprung up along the way both as a way of giving expression to their deepest passion and as a way of making sense of their understanding of Jesus.

Thus, most of the major justice initiatives of the last generation have been outsourced by the local church. Urbana Student Missions Conference, World Relief, World Vision, International Justice Mission, CCDA, Sojourners, Christians for Social Action are just a few of the incredibly powerful evangelical movements for justice that have generated enormous momentum and have helped mobilize a generation of Christians around the cause of justice.

If you spend much time in these circles, as I have, it is stunning to note how often people articulate a sense of family and homecoming when describing their experience of affiliation with these parachurch organizations. Over time, these groups have started to function as ecclēsia (church) for the justice-minded Christians who have experienced displacement from congregational life. I suppose this is a kind of double-edged sword. On the one hand, I am thankful for groups that create the spaces for followers of Jesus to work out their worldview into action in a safe and supportive community.

On the other, isn’t this reality a tragedy? Isn’t the fact that these organizations function as safe havens from the local church a devastating critique of the kind of people we have become? Justice organizations play a valuable and needed role in the world without question, but I mourn the role they are also required to play in the lives of many justice-minded evangelicals today because it evidences the severe deficiency of our local, embodied ecclesiology related to justice.

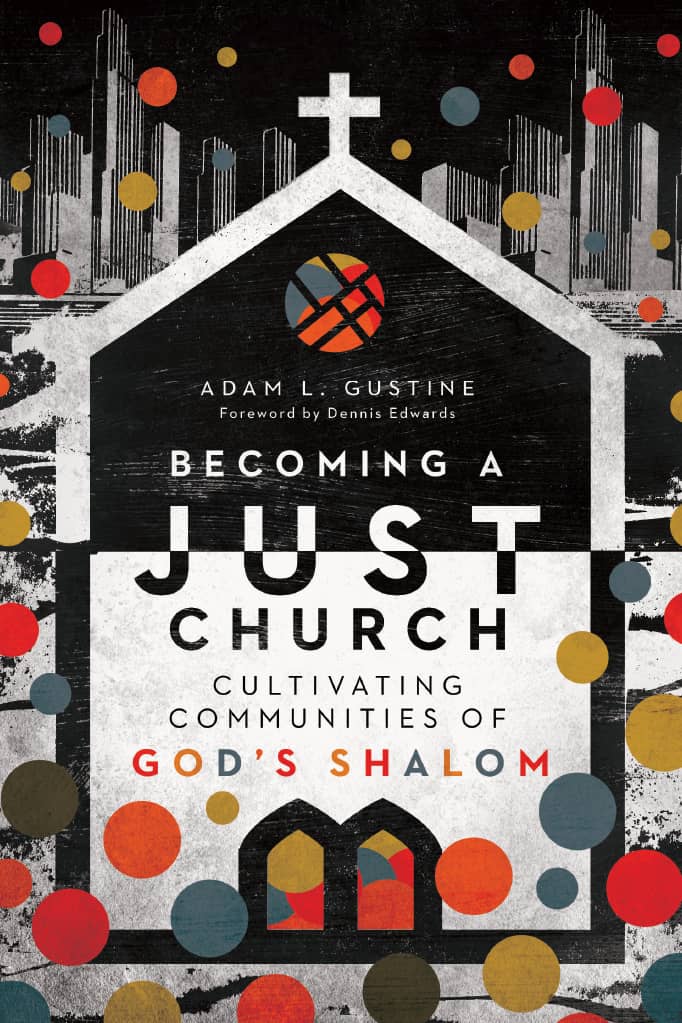

Becoming a Just Church is not just a critique of the current realities. Instead, in this book I aim to offer a vision for how the local congregation might regain its foothold in the work of justice and the pursuit of God’s shalom. In suggesting that there is a way forward, I suppose I am tipping my hand that I am an idealist when it comes to the local church. I cannot escape the reality that God intends for the kingdom mission to work in and through the church.

…God intends for the kingdom mission to work in and through the church.

That the missio Dei extends into the world through the local church is an exceedingly common sentiment these days in evangelicalism. There is a danger here, namely, that saying so can actually function to allow us to perpetuate our evangelical status quo without careful examination and reformation. In many cases, I experience it to be the case that this belief works to cosign our brokenness rather than make our knees quake in fear that the God of all creation would intend to work out the purposes of cosmic reconciliation and renewal through us.

I contend that the way we resist allowing this theological reality to function like a cliché is to be rigorously committed to self-examination as we lean into the reality of being the primary instrument of God’s purposes in the world today. If local expressions of the body of Christ are going to live into the fullness of God’s vision for the church, specifically as it relates to the pursuit of justice, much will need to change. And it will probably start with repentance.

Adam L. Gustine leads CovEnterprises, a social enterprise initiative of Love Mercy, Do Justice, for the Evangelical Covenant Church. He is also the founder of Jubilee Ventures, an enterprise incubator in South Bend, Indiana dedicated to extending opportunity, restoration and ownership to the margins. He has pastored multiple churches in a wide variety of contexts and has a doctor of ministry degree from Missio Seminary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He and his wife, Ann, are raising three kids to seek the shalom of their city South Bend. He is the author of Becoming a Just Church: Cultivating Communities of God’s Shalom, from which this excerpt is taken with permission from InterVarsity Press.

Adam L. Gustine leads CovEnterprises, a social enterprise initiative of Love Mercy, Do Justice, for the Evangelical Covenant Church. He is also the founder of Jubilee Ventures, an enterprise incubator in South Bend, Indiana dedicated to extending opportunity, restoration and ownership to the margins. He has pastored multiple churches in a wide variety of contexts and has a doctor of ministry degree from Missio Seminary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He and his wife, Ann, are raising three kids to seek the shalom of their city South Bend. He is the author of Becoming a Just Church: Cultivating Communities of God’s Shalom, from which this excerpt is taken with permission from InterVarsity Press.