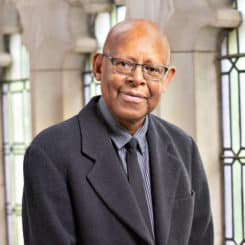

Dr. James Cone, the founder of Black liberation theology, passed away on April 28, 2018. Dr. Cone became famous during President Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign, during the controversy surrounding Jeremiah White. Dr. Cone’s theology was portrayed as the antithesis of sound biblical theology, but missing from that narrative is the profound impact he had on evangelicals, particularly evangelicals of color. In fact, it is safe to say that, despite the many faith challenges I have faced throughout my life, Dr. Cone is probably the person who most enabled me to still identify as an evangelical today.

…despite the many faith challenges I have faced throughout my life, Dr. Cone is probably the person who most enabled me to still identify as an evangelical today.

I became born-again when I was 16, and was very fundamentalist. While I was not politically conservative, I saw faith as focused only on individual piety—and hence focused only on improving my own personal morality in my walk with Jesus. Then one day, I was assigned James Cone’s God of the Oppressed, and my faith journey instantaneously changed. In particular, these quotes tremendously impacted me:

“But the will of God is not a set of rules and principles of behavior derived from a philosophical study of the ‘Good.’ We cannot know or hear the will of God apart from the social context of the oppressed community where Jesus is found calling for freedom…Theologians spend more time discussing metaphysical speculations about the origin of evil than showing what the oppressed must do in order to eliminate the social and political structures that cause evil…Theology is always a word about the liberation of the oppressed…Whenever theologians fail to make this point unmistakably clear, they are not doing Christian theology but theology of the Antichrist.”

I should note that I had previously read other theologians who also articulated more justice-based theologies, but these theologies were always accompanied by claims that the Jesus had not been resurrected, or that the Bible was full of errors. But Cone’s theology was consistent with what I saw as the important tenets of evangelical faith. That is not to say Dr. Cone identified as an evangelical, but that his theological interventions could harmonize with my evangelical beliefs.

Because of the influence of Dr. Cone’s work, I applied to Union Theological Seminary for an MDiv/MSW program. I had had a horrible undergraduate educational experience and swore I would never go back to school. I was not a good student, and had encountered no professors who thought I had any graduate school potential. However, after having worked as a rape crisis counselor and a social justice organizer for several years in Chicago, I reached the point where I was not sure if I was ending global oppression as expeditiously as possible. I thus applied for the MDiv/MSW program to contemplate the best way forward, as well as get academic credentials to continue in my work as a counselor. I went Union specifically to have the opportunity to work with Dr. Cone. In the end, this was a wise decision, as Dr. Cone provided me much more mentorship and support for my evangelical faith than evangelical churches have provided to me.

My first personal interaction with Dr. Cone came when, after taking a midterm in his Introduction to Systematic Theology, he wrote a note on my exam asking me to come to his office hours. When I did, he told me that he would not allow me to leave until I agreed to get a PhD. I explained that I did not really care for academia, since I thought academics were sell-outs, and he told me that was the reason why I needed to get a PhD.

My experience was not an isolated one. In my many years in the academic industrial complex, I’ve found professors generally prioritize high-achieving students with high GPAs and GRE scores. Most professors do not want to take the time to build student skills—they want students who essentially do not require much work or support. This generally ensures that students who have had the resources for more expensive schooling are prioritized for higher education. But Dr. Cone prioritized students who he thought had something to say, and took the time to teach them the skills they might not have. Dr. Cone was the first professor I ever had who thought I had any potential to have an academic career. This is why he was able to directly graduate more than 40 scholars of color with PhDs, as well as influencing countless other people of color who pursued PhDs with other mentors because Dr. Cone showed them that they had the ability to do it. Because of his mentorship, I learned that it was my responsibility to not only mentor the high-achieving student who might come my way someday, but to seek out students who have potential but who have never received the support or mentorship to develop intellectually.

One of the reasons Dr. Cone graduated so many students of color was that he did not just focus on our academic skills, but helped us develop our skills to navigate the academic industrial complex and to invest in more than careerism. Alexia Salvatierra and Peter Heltzel’s Faith-Based Organizing discusses the importance of engaging in what the authors call “dove and serpent power” in advocating for social justice. As the book states, organizing must be done in a manner that is cognizant of how systems of domination operate: “Jesus did not call us to be only innocent as doves, he also called us to be wise as serpents,” which requires us to not only act faithfully but to “act strategically.” Dr. Cone was an exemplar in teaching students to be strategic. I as well as numerous students of color had many challenges at Union. But Dr. Cone advised us, “Just because someone smiles at you doesn’t mean they like you.” He taught me to look beyond the surface of what people say and watch what people actually do.

Dr. Cone also taught me not to internalize negativity in academia. One time I came to him upset because I had unintentionally offended a professor, yet again, by simply disagreeing with him. I asked Dr. Cone for some diplomacy lessons. His words, which have centered me throughout my life, were: “Andy, if you’re not pissing people off, it’s because you’re not saying anything.” Through him, I learned that having justice-based commitments does not necessarily lead to popularity, and thus I learned to accept the fact that a commitment to Christ is always a risky commitment.

Having been persuaded by Dr. Cone to begin a career in academia, he enabled me to do this work as an evangelical even within a liberal seminary. I found that people of color are often excluded in both conservative and liberal seminaries on the basis of a variety of theological, political, and social litmus tests. Because people of color often articulate theology and politics from a different perspective from the white mainstream, they are never either properly liberal or conservative. I have come to see all these litmus tests as racially coded tests, designed to ensure the whiteness of seminary culture, whether the seminaries are liberal or conservative. But Dr. Cone was able to work with people of color across political and theological perspectives.

I often talked with Dr. Cone about his long-standing collaborative relationship with the National Black Evangelical Association. As William Pannell asserted during the beginnings of the racial reconciliation movement, Dr. Cone “made black evangelicals question their long flirtation with mainline evangelical institutions, institutions that seemed unwilling to acknowledge the problems and feelings of black brothers and sisters.” (The Coming Race Wars?). Thus, while white evangelicals painted Dr. Cone as the antithesis of evangelical faith, especially during the Jeremiah White controversy, in fact Dr. Cone’s impact on the theologies of evangelicals of color is deep. He did not require students to pass any litmus tests to be supported and mentored by him.

Besides supporting my evangelical faith, Dr. Cone actually strengthened it. Dr. Cone taught me to have faith based on courage rather than fear, and not to be afraid of questions and challenges.

Besides supporting my evangelical faith, Dr. Cone actually strengthened it. Dr. Cone taught me to have faith based on courage rather than fear, and not to be afraid of questions and challenges. I was very fundamentalist when I went to Union, and the Bible classes really shook my faith. At one point during my first semester, I was in bed for a week suffering from a faith crisis. But when I took Dr. Cone’s class, he told us to read Marx, Feuerbach, and anyone who sharply critiques Christianity. He said, “If you can’t read all the masters of suspicion and have your faith shaken to the core and come out on the other end, then your faith doesn’t mean anything.” He enabled me to develop a faith that could embrace, rather than shy away from, challenge.

Finally, Dr. Cone personified what it meant to be a prophetic voice for justice. When I was at Union, we had a bit of people of color uprising that did not make the faculty happy. Since I was the student representative at a faculty meeting, many faculty members were screaming at me, tearing me apart, calling me all sorts of names. It was not pretty. But even though Dr. Cone didn’t even initially agree with our position, he sat down and listened to us, and change his mind. I remember him telling the faculty, “Look, I didn’t agree with this position either, but when all the students of color told me I was wrong, I had to hear what they were saying. And you all should listen, too.” Dr. Cone always chose being prophetic over being polite.

At the same time, Dr. Cone also demonstrated that being truly prophetic requires the ability to change. I learned from him the importance of being able to admit mistakes, change, grow, and also to make those changes and mistakes transparent. In all of the prefaces to his revised books, Dr. Cone details the things in the books he no longer agrees with, the political challenges to his work that he embraces, and the shortcomings in his previous political and theological visions. His work in general always admits and contemplates his previous mistakes.

Similarly, in class, Dr. Cone always provided his own intellectual and political genealogy of change that got him to the present point. He showed that having a strong political vision was not inconsistent with hearing others and admitting when you are wrong. I learned from him that my writings don’t have to stand for all time, and that their contribution is part of a larger conversation about liberation that may eventually leave my work behind, rather than an object that has to be defended against challenge.

There are countless times I wanted to leave evangelicalism based on the rampant racial and gender violence I witnessed from church leaders. But Dr. James Cone enabled me to stay. As he stated, theology’s great sin is silence in the face of white supremacy. But he not only articulated a different theology based on justice, he personified it. May we all live into his legacy.

Andrea Smith is the coordinator of Evangelicals 4 Justice and a board member of the North American Institute for Indigenous Theological Studies. She is the co-editor, with Mae Cannon, of Evangelical Theologies of Liberation, forthcoming from InterVarsity Press. She currently serves as acting chair for the Ethnic Studies Department at UC Riverside.