Stepping Over a Homeless Man to Feed a Dog (And Other Things I’ve Never Had to do as an Animal Advocate)

I’ve been an activist since I was old enough to walk. For most of my life, my passion was poured into the pro-life movement. When I was 4, my parents took me to a pro-life rally at the Idaho capitol building, and our picture made the front page of the newspaper. In middle school, I was president of a drug education club. In high school, I presided over the local Teens for Life group, worked tables for Oregon Right to Life at local events, performed pro-life songs and plays at rallies, and attended packed statewide pro-life conferences. None of my Christian friends and family ever questioned whether or not the defenseless beings I was working to protect needed or deserved my help. It was (and continues to be) my calling to be a voice for the voiceless, to stand up for justice and life in the face of a culture that systematically finds ways to prevent lives from truly flourishing.

I’ve been an activist since I was old enough to walk. For most of my life, my passion was poured into the pro-life movement. When I was 4, my parents took me to a pro-life rally at the Idaho capitol building, and our picture made the front page of the newspaper. In middle school, I was president of a drug education club. In high school, I presided over the local Teens for Life group, worked tables for Oregon Right to Life at local events, performed pro-life songs and plays at rallies, and attended packed statewide pro-life conferences. None of my Christian friends and family ever questioned whether or not the defenseless beings I was working to protect needed or deserved my help. It was (and continues to be) my calling to be a voice for the voiceless, to stand up for justice and life in the face of a culture that systematically finds ways to prevent lives from truly flourishing.

During college, I started to read about factory farming, which is the way that billions of animals that end up on North American plates are raised and slaughtered. My images of happy animals on Old MacDonald’s farm were shattered and replaced with dark new ones: miserable lives all ending in the same nightmarish way, hung upside down on a fast-moving slaughter line, throat slit, waiting to die. I stopped being able to look at the chicken on my plate as food and started to realize that when I ate meat, my meal had stopped a beating heart.

I started to work for animals. I didn’t stop loving Jesus. I didn’t stop advocating for peace and life for humans everywhere. I just started to advocate for nonhuman animals, too. And when that started, so did the pushback: “Aren’t there other things that are more important?” “What about the starving kids in Africa?” “Shouldn’t you work to solve all of the human problems first?” “What, are you going to step over a homeless dude and feed his dog?”

I understand the concern. One of my closest friends spent a lot of time in foster homes as a teenager. He and houses full of kids without families would be watching TV and hear the familiar Sarah McLachlan refrain as pictures of abused and homeless dogs and cats flashed across the screen. He still gets pretty fired up at the memory and says he’ll be happy to start worrying about homeless dogs and cats as soon as people start airing commercials for homeless kids. I totally get it. But here’s the thing—if God is calling you to reduce homelessness, dig wells in Africa, fight poverty, minister to the dying, stop sex trafficking, fix a broken education system, reduce gun violence, foster world peace or racial reconciliation, or any other Really Godly Uses of Time, you can do any of that and still help stop cruelty to animals. One vegetarian saves more than 100 animal lives a year. Period. No protesting, tract-handing-out, quitting-of-full-time-job-level sacrifices required. Helping animals and helping people are not mutually exclusive propositions. In fact, they are closely linked.

Meat Wastes Essential Water and Grain

Eating meat wastes valuable and increasingly limited resources. It takes up to 13 pounds of grain plus another 30 pounds of grasses to produce just a pound of meat. (1) Do you want a pound of animal protein? That’ll use 100 times more water than a pound of plant protein. Studies have shown that up to 5,000 gallons of water are required for every pound of beef. (2)

That’s what it takes to produce. Here’s who we kill and eat: 61,644,000 cows, 9,152,269,000 chickens and turkeys (9 billion birds) and 234,776,00 pigs. These aren’t worldwide figures—those are federal slaughter figures for the United States in 2016. That means billions upon billions of pounds of grain and millions of gallons of water were pumped into animals to produce a limited and costly food source for a (largely) well-fed populace instead of being distributed directly to hungry, thirsty people throughout the world. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reports that approximately 793 million people in the world are undernourished.

Jesus tells his disciples, “When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him…he will say to those at his left hand, ‘I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink…Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me’” (Matt. 25: 31-46). Take a few minutes to read the whole passage and then reread the disturbing facts above.

The Global North is often accused of using far more than its fair share of resources. We vow to change the kind of light bulbs we use, drive a little less, take reusable shopping bags to the grocery store, recycle our pizza boxes and water bottles…these are all valuable changes, but they barely make a dent when we continue to chow down on animals.

In the first chapter of Genesis, God prescribes a vegetarian diet for human and nonhuman animals alike and calls the created world “very good” (Genesis 1:29-31). In the second account of the creation story, God tells the human creatures to “till and keep” the garden (Genesis 2:15). We are tilling the garden, but we aren’t doing a very good job of keeping it. In the United States, about 60 percent of our pastures are overgrazed, and soil erosion is accelerating at an unsustainable pace. (3) The land simply isn’t made to sustain billions of people relying on a diet of animal products.

It would be bad enough if we were wreaking this havoc just on our own soil, but globalization has exported more than cheap and dangerous clothing manufacturing to the majority world. In an effort to keep pace with the global market and capitalize on an export market hungry for animal protein, the Brazilian Amazon has become, according to Greenpeace, the “largest driver of deforestation in the world, responsible for an average of one acre lost every eight seconds.” Greenpeace researchers found that in the 2004-2005 growing season alone, 2.9 million acres of rainforest were destroyed to raise crops used to feed animals on factory farms. Meanwhile, Oxfam reports that 66 million Brazilians face daily food insecurity. These are just a few examples of the global failures of today’s food production methods.

God Made the Whole World

I think sometimes we forget that God made the whole world, including the chickens and the turkeys. I think we forget, because why else would we think it was okay to do some of the things we do to animals before we eat them? I have a special affinity for chickens, so let’s talk about them for a few minutes.

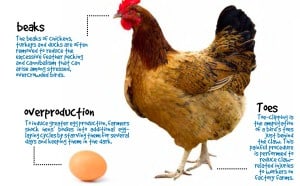

Chickens raised and killed for their meat on factory farms are hatched in drawers and dumped onto the floor of a giant shed where they stay for two months until they are “fully grown.” As the chickens grow, quarters get tighter and tighter, and the accumulation of feathers, feces, and urine creates toxic air and can become so dangerous that chickens get ammonia burns and workers must wear protective clothing and respirators to safely enter the sheds. (4) Chickens naturally establish dominance through pecking orders, but in such cramped quarters, pecking can be quite harmful. To prevent this natural behavior, workers use hot blades or wires to cut the beaks off of baby birds. Because we have developed an affinity for breast meat, chickens are bred to grow too fast, and their legs often cripple beneath them. (5)

Egg-laying hens are crammed into cages about the size of a file cabinet. They each have less room than a sheet of paper on which to live. They eat, sleep, and defecate in this small space and are unable to stretch their wings. Cages are stacked one on top of the other in huge warehouses; you can imagine what that looks, feels, and smells like. Egg-laying hens live this way for an average of two years before their bodies will no longer produce enough eggs to be worth keeping. Dead and dying chickens are rarely removed.

The first time most chickens feel the sunshine or breathe fresh air is when they are on the back of a truck, headed to slaughter. To gather chickens for transport to the slaughterhouse, workers walk through the sheds, grabbing birds and flinging them into crates; this frequently breaks wings and legs. At the slaughterhouse, the crates are dumped onto conveyor belts from which workers grab birds and slam their legs into shackles at the rate of 140-180 birds per minute per line. (6) Their heads are sent through an electric stunning bath (which often does not render them insensible to pain), and then they are run across an automatic blade, which frequently misses the bird’s throat, maiming them instead. Many chickens and turkeys are still alive when they enter the scalding tank for feather removal, meaning they drown to death in boiling water.

While I have focused on chickens, the foundational view of animals as commodities and resulting methodologies are found across the entire industry, and parallel abuses will be found in an examination of cow, pig, or fish farming. What I have described is standard agricultural practice, meaning these practices are common, accepted, and legal. What I have not described are the grotesque abuses exposed by undercover investigations of farms and slaughterhouses by animal advocacy groups, such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and Mercy for Animals.

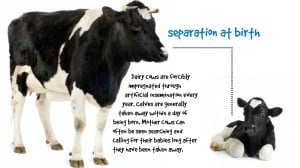

Factory farms are only “successful” because they dramatically alter God’s original creative design. We have seen many examples of this in explorations of chicken farming: Birds are unable to stretch their wings; they are denied the small pleasures of fresh air, sunlight, pecking for food, or social interaction; and they are genetically modified to a crippling degree. Cows, chickens, pigs, and turkeys that would otherwise forage for a variety of foods are given a manufactured diet of grain spiked with antibiotics. To keep pigs from biting one another and chewing on their cage bars, their teeth and tails are cut off. Pigs and cows are castrated without painkillers, and cow’s horns are scooped or burned out of their heads. These acts are not only cruel, but they also dishonor God’s creative plan and betray our selfish and power-hungry tendency to elevate our own wants and desires at any cost.

The British theologian Andrew Linzey claims that a strong Christology leads to a view of nonhuman animals that doesn’t allow for these types of uses or abuses. “The pattern of obligation disclosed by Christ makes no appeal to equality. The obligation is always and everywhere on the ‘higher’ to sacrifice for the ‘lower’; for the strong, powerful, and rich to give to those who are vulnerable, poor, or powerless.”(7) Jesus came to us as a humble servant (c.f. Mark 10:45, John 13:1-20, Acts 3:13, Philippians 2:5-9). Consider again the passage from Matthew 25—what we do to the “least of these” we do to Jesus. When we are in positions of power, we are called to serve.

Christianity and Factory Farming

One striking example of the power of service is in the story of the Good Samaritan. When the story begins, Jesus is teaching a small crowd. A lawyer asks Jesus how he can inherit eternal life. We’re told the man is testing Jesus, who responds as a teacher does, with a question: “What is written in the law?” The lawyer answers, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind and your neighbor as yourself.” Jesus commends him, but the lawyer pushes back: “And who is my neighbor?” In this context, we hear of the man who was traveling a dangerous road and overcome by robbers. He is passed by a priest and a Levite (examples of highly respected citizens) before the Samaritan stops, is “moved with pity,” and saves him from certain death. Jesus asks the lawyer which of the three was a neighbor. The lawyer answers, “The one who showed him mercy,” and Jesus tells his listener to “Go and do likewise.” In this story, the hero is the person who crosses the road and saves the life of another—and he is a Samaritan—a no-class, unclean, bottom-of-the-barrel foreigner. (8)

Through the lens of this parable, through the lens of Jesus, “neighbor” is not a social location but action—and specifically love in action. Using a Samaritan to illustrate neighborly love was a game-changer in 1st-century Palestine. It was astounding to think that a barbaric Samaritan could demonstrate love, and unthinkable to cross the rigid cultural boundaries that prevented showing mercy or friendship to the “other.” Perhaps it is just as astounding to consider crossing rigid species boundaries to extend mercy and friendship to nonhuman animals. But consider that as each era passes, humans realize past injustices (slavery, child labor, the subjugation of women, the wanton abuse of natural resources) and work to rectify them.

The parable of the Good Samaritan is not the only place Jesus makes the outrageous claims to expand our circle of compassion and care (remember “Love your enemies”?). We are to respond in love to those who persecute us, who want to murder us and our families. How much more is our obligation to respond in love to the vulnerable creatures God has placed in the world alongside of us? Theologian and ethicist Daniel Miller points out that “granting neighborly love to animals does not lead to a diminishment of the Christian’s capacity to love human neighbors.”(9) Indeed, doesn’t our capacity for communion with God and neighbor, and our ability to freely respond to injustice in our world, demand from us care rather than cruelty?

Jesus didn’t ask us to love some times and hate other times. Jesus didn’t ask us to be merciful when it was convenient and to turn a blind eye when we felt uncomfortable. Jesus didn’t ask us to categorize and prioritize and show love to the top first—and then to the bottom if we had any energy left at the end of the day. Jesus didn’t ask us to have the bleeding victim of greed answer a three-part questionnaire to determine his worthiness before intervening on his behalf. Jesus tells us that neighborly love is merciful love, regardless of the giver or the recipient, and that we are to go and do likewise.

Sarah Withrow King is CSA’s deputy director and the co-director of CreatureKind, a project that engages the church on farmed animal welfare issues. She has a Masters in Theological Studies from Palmer Theological Seminary and is the author of Animals Are Not Ours (No, Really, They’re Not): An Evangelical Animal Liberation Theology (Cascade Books, 2016) and Vegangelical: How Caring for Animals Can Shape Your Faith (Zondervan, 2016).

Endnotes:

- David Pimentel and Marcia Pimentel, “Sustainability of Meat-Based and Plant-Based Diets and the Environment,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78: 3 (September 2003), 662S.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 662S.

- Leo Horrigan, et. al, How Sustainable Agriculture Can Address the Environmental and Human Health Harms of Industrial Agriculture, 451.

- I.A. Naas, et al, “Impact of Lameness on Broiler Well-Being,” The Journal of Applied Poultry Research 18:3 (Fall 2009), 432-439.

- SF Bilgili, “Recent Advances in Electrical Stunning,” Poultry Science 78:2 (1999): 282-286.

- Andrew Linzey, Animal Theology (University of Illinois Press, 1994), 32.

- Luke 10:25-37, NRSV.

- Daniel K. Miller, Animal Ethics and Theology: The Lens of the Good Samaritan (Routledge, 2012), 15.