What happens when faith is co-opted for power? We are far from the first Christians to find ourselves forced to address this question. In A People’s History of Christianity, historian Diana Butler Bass traces 2,000 years of push and pull between one version of Christianity that cozies up to power—or seeks to seize it outright—and another version that sides with the people oppressed by this very same power.

What happens when faith is co-opted for power? We are far from the first Christians to find ourselves forced to address this question. In A People’s History of Christianity, historian Diana Butler Bass traces 2,000 years of push and pull between one version of Christianity that cozies up to power—or seeks to seize it outright—and another version that sides with the people oppressed by this very same power.

“From Constantine to Christendom to the Christian Right,” Butler Bass reflects, the story of the church can feel “remarkably depressing for thoughtful and sensitive souls.”

“This dismal historical record,” she continues, “surely was not what Jesus intended as he preached a merciful kingdom based on the transformative power of God’s love.”[1] Jesus taught—and, crucially, lived—a way of transformative love. But after his death, people acting in his name began to pursue a different path entirely.

Our current form of Christian nationalism is simply one more iteration of a pattern that can be traced back through the entirety of Christian history. And there have always been those who have opposed it. St. Martin, for example, in the 4th century, petitioned to leave his job in the Roman army, saying, “I am Christ’s soldier; I am not allowed to fight.”[2]

In the 12th century, Hildegard of Bingen exhorted the church toward justice, based on her belief that “the whole universe was her neighborhood,” and “everything was really one, interwoven life that demanded justice for all.”[3] Christians today who resist nationalist ways of violence, dominance, and oppression take up a calling that many faithful ones have pursued before us. Our predecessors can inspire us and show us the way.

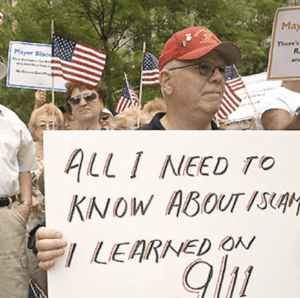

Resistance to nationalism might look different for each of us, but it includes taking an honest look at Christian history—and at American history, too. Writer and activist Lisa Sharon Harper says this: “Scales fell from White eyes in 2020 and in the early days of 2021. We saw who we are and realized we can choose the nation we will be. There is only one condition: We must reckon with the nation we have been—all of it.”[4]

Harper invites us all—and especially those of us whose communities have profited from America’s racialized violence and white supremacy—to face our collective past truthfully, that we might be able to move together toward repair. We resist nationalism by being honest about our nation’s failure to live up to its stated ideals of liberty and justice for all, both in the past and present.

As Choctaw theologian and retired Episcopal bishop Steven Charleston writes in We Survived the End of the World, “There are no shortcuts to reconciliation. No quick fixes. No magic. Only honesty and hard work, facts and figures, accountability and responsibility, justice and acts of restoration.”[5] When we engage in the work of justice, in ways large or small-seeming, we are actively resisting a nationalist narrative that pretends our nation does no wrong, that we are in fact unified under God, that whatever we do must be right because God is on our side.

In a time when our current U.S. administration is instigating war abroad and violently gutting basic social services at home, we can expose the lies of those who say, in the words of the prophet Jeremiah, “‘Peace, peace,’ when there is no peace.”[6] The wounds of Americans of color, of queer and trans Americans, of Americans living in poverty, of American women, of immigrant Americans and international students, of American protestors—as well as the wounds of children and adults across the world harmed by America’s violence—none of these wounds are light. We resist by refusing to treat them lightly.[7]

Even as we examine our shared history and present reality, we can also look inward, sorting through our own beliefs and behaviors, looking to keep what points us toward love and justice and grow beyond anything that serves the purposes of fear and authoritarianism.

Reflecting on her teenage years in white-dominated evangelical spaces, Potawatomi author and poet Kaitlin B. Curtice writes, “I had adopted a nationalistic view of God and of my Christian responsibility, as well as the message that as a woman my place is in the home, supporting whomever my future husband would be…Without knowing it, I had adopted colonial, militaristic, patriarchal views of God, and for me as a woman, these views translated into people-pleasing and a fear of authority.”[8]

What does authoritarianism look like when it lives within us? Perhaps while those who hold power in our current system resist by reexamining this power, those who have been told they should not hold power resist by rethinking their default tendencies to submit. As we learn to resist inappropriate, harmful, or unnecessary authority in small ways in our daily lives, we practice resisting authoritarianism more broadly. We eschew people-pleasing, becoming more fully who God created us to be and courageously doing the good we can do in our world.

As we seek to resist nationalism, we hold in front of us a vision of a different kind of world. We imagine a world defined not by white supremacy, patriarchy, and militarism, but by equality, justice, and peace. We build something different in our own lives, families, friendships, neighborhoods, schools, churches—in every sphere where we might have the power to do so.

The forces of nationalism are strong, but they are not irresistible. We can draw strength and inspiration from those who have resisted in the past. We can learn and tell the truth about Christianity and about America.

We can continue to find, encourage, and accompany one another on the path of transformative love. And we can experience the joy of being in this together. Sustaining resistance for the long term demands nothing less.

References

[1] Diana Butler Bass, A People’s History of Christianity: The Other Side of the Story (New York: HarperOne, 2010), 2.

[2] Ibid., 71.

[3] Ibid., 131-2.

[4] Lisa Sharon Harper, Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World—And How to Repair It All (Ada: Brazos Press, 2022), 173.

[5] Steven Charleston, We Survived the End of the World: Lessons from Native America on Apocalypse and Hope (Minneapolis: Broadleaf Books, 2023), 135.

[6] Jer 6:14

[7] Ibid.

[8] Kaitlin B. Curtice, Living Resistance: An Indigenous Vision for Seeking Wholeness Every Day (Ada: Brazos Press, 2023), 118.

Liz Cooledge Jenkins is a Seattle-based writer, preacher, former college campus minister, and the author of Nice Churchy Patriarchy: Reclaiming Women’s Humanity from Evangelicalism. She writes regularly at growingintokinship.

Liz Cooledge Jenkins is a Seattle-based writer, preacher, former college campus minister, and the author of Nice Churchy Patriarchy: Reclaiming Women’s Humanity from Evangelicalism. She writes regularly at growingintokinship.