A curious feature in American evangelicalism (which is different from Canada on this notable factor) is self-conferring the position of protector and gatekeeper to all Christian truth. This posture produces a certain response when theological or cultural presuppositions are challenged. When it comes to deconstruction, a slew of pastors, theologians, and other thought leaders are working hard to discredit the growing movement.

A curious feature in American evangelicalism (which is different from Canada on this notable factor) is self-conferring the position of protector and gatekeeper to all Christian truth. This posture produces a certain response when theological or cultural presuppositions are challenged. When it comes to deconstruction, a slew of pastors, theologians, and other thought leaders are working hard to discredit the growing movement.

There is an obvious disconnection between the chorus of voices restless for wholeness and the so-called “protectors” of religious orthodoxy whose bias is to preserve the institution.

From inside the safe confines of the church walls, systemic problems are ignored at best, or hidden at worse. From the inside, liberation for all people is not an objective—protecting power and tradition is. That includes conservative voices (who decry deconstruction as dangerous, bordering on anathema) and progressive ones, too (who water down deconstruction to preserve the institution). Of course, having particular convictions is not a problem—every denomination has them—but assuming those convictions are absolutes that everyone must adhere to is.

Virtually all denominations have seen a decline in membership for well over a decade. (Some mainline denominations have been declining unabated for 60 years.) This does not even begin to factor in the catastrophic losses of the global pandemic. Shouldn’t church leaders, in our current reality, focus on the causes of decline rather than turning “deconstruction” into a pariah? Perhaps the simplest answer is the best one in this regard. Institutional Christianity has a vested interest in deconstruction, because their own people (or the ones they have lost) are the ones deconstructing!

I often remark how the social media hashtags #exvangelical and #deconstruction (more so the former) are dominated by white thought leaders. I have an issue with this exclusivity but not with the demographic reality. White evangelicalism (and therefore white churchgoers) was a majority tradition in the United States. It’s no surprise that white Christians, or those who used to be Christian, are sharing their stories of encountering and confronting the various forms of abuse and toxicity. This is why we must question the motives of church leaders decrying deconstruction.

There is more concern about the loss of inherited privilege in the day-to-day lives of Christian adherents than about addressing malformed roots.

Ultimately, those questioning past faith experiences are rightfully processing all that detracted from the fullness of life, and are too busy tending wounds to pay attention to vain warnings from within.

The difference between deconstruction and reformation

I should note my view on deconstruction is biased as well, influenced by my journey and work in vocational ministry outside of institutional boundaries. For instance, I don’t believe deconstruction means reformation. Reformation talk generally means preserving or merely shifting the institution.

Deconstruction cares not about the preservation of power. Rather, it fundamentally interrogates the structures producing the power and inequality in the first place. That’s not initially a call for destruction; rather, it’s an understanding that liberation requires examining structural elements, then being prepared to cut away any infection.

Deconstruction dares to ask, in the pursuit of individual and collective wholeness, whether the institutional church is worth saving. If this process leads to the collapse of an institution, then that indicates there was little worth saving. The internal rot must have been so widespread that self-destruction was imminent. Ultimately, the fear of and concern with deconstruction emanating from inside the church hinders the discovery of malformed roots, producing harm that may not be redeemable.

Therefore, there’s no coordinated deconstruction effort bent on destroying churches or denominations. Rather, the growing number of individuals engaging in deconstruction indicates widespread internal problems. When more and more Christians begin to survey all that ain’t right in their faith, obvious conclusions are made. Among them is to simply leave, and when enough pews are emptied, the entity starves.

Deconstructing out of faith and community becomes the decision caused by harms worth escaping.

Deconstruction as faith reclamation

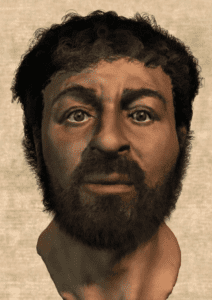

This is not to say deconstruction leads to de-conversion or renouncing faith. In fact, I champion the opposite. My work in deconstruction has resulted in a way back. Not back into the institution (although it could happen), but rather back to Jesus. Not white Jesus created in America or Europe, but the multiethnic brown Middle Eastern man who is God and who unceasingly stood with the marginalized because he, too, was on the margins. The Jesus who deconstructed culture and religion every time he proclaimed, “you’ve heard what was said,” and followed it up with, “but I say to you. . . .” That’s who we seek to reclaim, as the subtitle of this book suggests.

I believe reclamation is worth it and that this work offers more possibilities for future wholeness than leaving it all behind. The fear is realizing you’re deconstructing alone in uncharted territory. But the feeling doesn’t have to last long. Take your time to find your bearings, and when you do, turn your head up and find out you’re not alone at all. There are countless people in communities around the globe asking the very same questions you are, and it is good. Of course, that doesn’t mean I don’t hear friends, or people online, hitting a wall in their journey and exclaiming, “I’m done with Christianity!”

But I want to call back and say, There’s still hope out there! If there were good pieces in our faith worth reclaiming, would you be interested in the possibility? With this in mind, here is my invitation into the grey space of deconstruction and the possibilities to reclaim new life.

Excerpted from When We Belong: Reclaiming Christianity on the Margins (Herald Press, 2022). All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Rohadi Nagassar is a writer, entrepreneur, non-profit developer, and pastor. He lives on Treaty 7 Land in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. He currently writes in the areas of anti-racist discipleship, diversity and inclusion, deconstruction, and decolonizing the church. His books include When We Belong: Reclaiming Christianity on the Margins, Soul Coats: Bible Themed Adult Coloring, Thrive: Ideas to Lead the Church in Post-Christendom, and #changethestory: A Short Resource on Dismantling Racism in the Church. Visit him at rohadi.com for more, including his podcast, Faith in a Fresh Vibe.