We all cherish the picture of Jesus eating with the “disreputables”—the tax collectors and prostitutes and other sinners. But what do we do when the offensive offend us?

Our first night in Johannesburg, South Africa, did not go well. It was long past suppertime, and we weren’t sure where to stop for food. I had forgotten how to drive a stick shift and crashed our rental car into the gate at the bed-and-breakfast where we were to stay.

At long last we settled into our room and then adjourned to the patio, gazing at the garden while the white proprietor got us oriented. I asked him about securing a guide to take us to Soweto, the sprawling black township that served as a prime setting for the end of apartheid.

He set his jaw and said, “You don’t want to go there. They live there.”

I was in no mood for the quandary that faced me. Yes, I know, God wants us to oppose racism—vigorously—in all its forms. Justice demanded a response to set this fellow right. But I am conflict-averse to the extreme.

More than that, I was all too aware of my status as an American on his very first night in a country with a wildly complex racial dynamic.

So I took the easy route and kept my mouth shut. I did not do what Jesus called me to do.

Or did I?

When the Offensive Offend Us

We all cherish the picture of Jesus eating with the “disreputables”—the tax collectors and prostitutes and other sinners. It illustrates his boundless love for “the least, the last, and the lost.” The scene in my mind is lit like a Rembrandt, all rich, dark, and glowing. The sinners may look bedraggled, but they are decent people.

Or so we might think. In fact, the gospel passages do not tell us much about the individuals at these dinners beyond their status in society. We don’t know what they said or what they believed. Maybe the tax collectors were virulently anti-Jewish. Perhaps the prostitutes told cruel jokes about lepers.

What would happen if they did? Would that make us recoil in horror? Should it? Are there people whose opinions and beliefs are so vile that we should close our ears and hearts to them? If not, how do we guard our hearts from the influence of those beliefs while reaching out in love?

In discussions of this kind, the catchphrase “hate the sin, love the sinner” inevitably comes up. Whatever value it might have in other contexts, it is unhelpful here. If our love is to be concrete—loving not “the sinner” but this sinner sitting with us on the patio or at a meal—we have to listen. Often, when we listen with full attention and a loving heart, the other person responds by trusting us, and we will hear more of what’s in his heart, quite possibly including racism and vengefulness and all manner of dross.

Besides hearing things that we know are wrong, we will also hear things that we think we know are wrong—or they are wrong, but there is more to the story. We Americans are quite sure that all terrorist organizations are evil. Yet the picture gets muddy when we consider that some of these organizations, like Hamas in Gaza, provide social services to the poor even while calling for the extinction of Israel.

As it turned out, there was more to the story of our racist innkeeper. The day after our first conversation, his wife invited us in for tea, and she shared the story of how they came to South Africa. For years they had operated a lodge in neighboring Rhodesia, but when Rhodesia became Zimbabwe—ushering in the black-majority government of Robert Mugabe—they received threats of land confiscation and physical harm. Eventually, she said, they escaped to South Africa with their lives.

Suddenly a light went on in my mind. I did not stop believing that racism was wrong. But for the first time in my life, I could see how someone with this kind of experience could adopt racist views. I could have compassion for their suffering without losing my joy in a post-apartheid South Africa.

In short, I could love a racist. If I had spoken up the night before, taking the innkeeper to task for his racism, what are the chances I would have heard their story?

The Work of the Soul as our Surest Defense

So in one limited instance, I could see racism as understandable. Is that a slippery slope, at the bottom of which I might learn to tolerate racism?

Here, I believe, lies our biggest advantage as Christians. Over time our relationship with God conforms us more and more to God’s image. In other words, the closer we draw to God—the more we cultivate our love relationship with prayer and silent listening and the study of Scripture and all the other life-giving “tools” of our faith—the more room we give God to align our deepest selves with divine wisdom and virtue. Rather than simply defend truth and compassion and good, we become truth and compassion and good.

In the process, God’s reorientation of us becomes the unshakable core that keeps our hearts safe, allowing us the freedom to explore all points of view without fear. Because of this, we can throw open our hearts to welcome even the most disreputable, listen to their stories, and enable them to feel valued.

I do not know whether our innkeepers valued our time together. For me, however, the experience added even more depth to Jesus’ command to love everyone wastefully, extravagantly, no exceptions, knowing I am safe in the arms of God. If I had not kept my mouth shut, I might have missed one of the most important lessons I have ever learned.

John Backman is a spiritual director, contributor to Huffington Post Religion, and associate of an Episcopal monastery. He writes about contemplative spirituality and its surprising relevance for today’s deepest issues, and is the author of Why Can’t We Talk? Christian Wisdom on Dialogue as a Habit of the Heart.

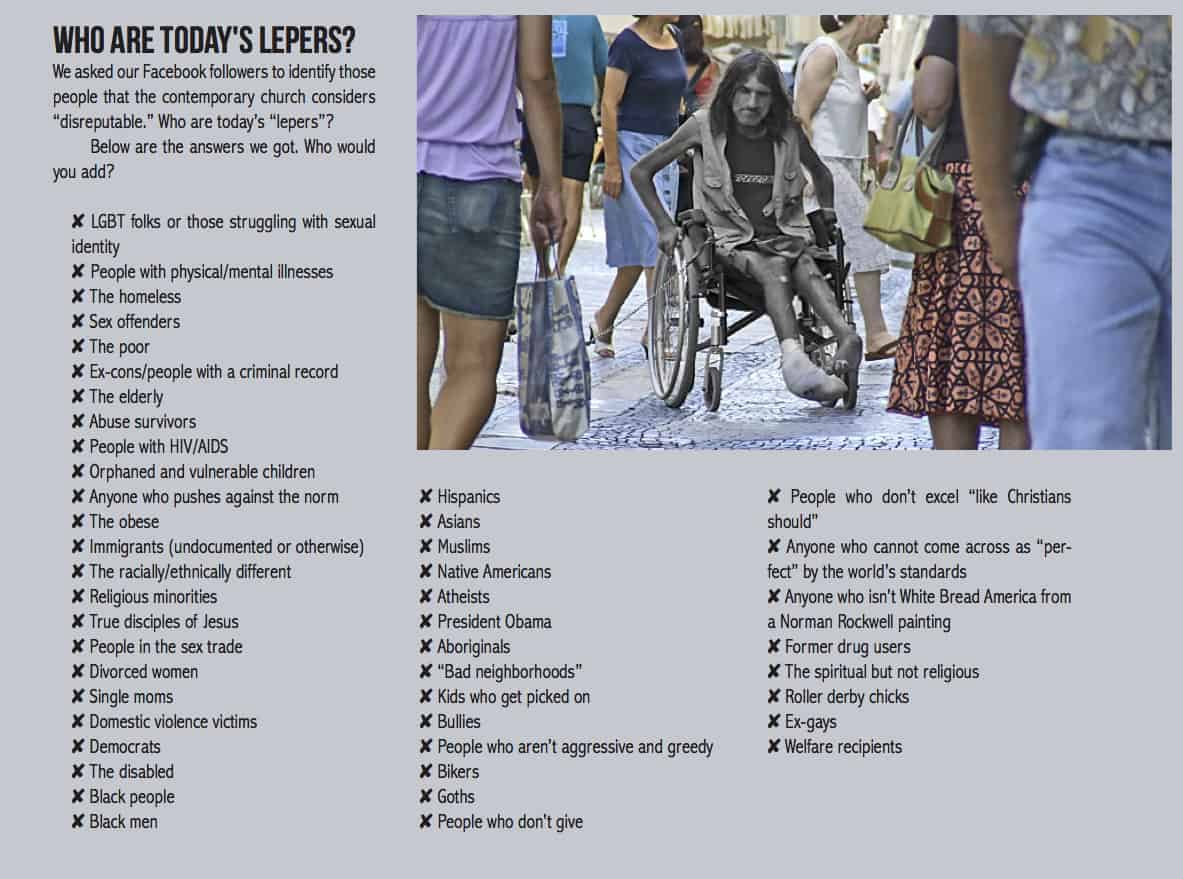

Who Are Today’s Lepers? (click to enlarge)