Last week, our pastor started his fourth Sunday sermon in an ongoing series about prayer. I held my pen ready over my notebook, eager to learn something new. He told us we were going to focus on The Lord’s Prayer, or what the Catholic tradition calls the Our Father. I put my pen down and quietly sighed. I memorized that prayer 40 years ago.

Our pastor reminded us how shocking it was for Jesus to teach his disciples to call Yahweh, the King and Master of the Universe, “Father.” He challenged us to talk to God differently all week, instead calling him “The Dad Who Loves Me” or, because we’re in the South, “My Lovin’ Daddy.” Or, to simply beg, “Papa, Help Me!” Because that’s what “Abba” means, the Aramaic word Christians sometimes hear referring to God in modern worship choruses.

The sermon faded to a muted buzz as I remembered a passage from the book I devoured the night before:

That’s when I recognize one word the little boy is using, hidden among the chatter of his Arabic. It’s a word that leaps out to me, a word I have heard before but never in the wild. Never being used in its native language.

Abba.

“Abba,” he begins pleading in a soft voice, before chattering on in Arabic.

Abba. I have never heard this word used between an Arabic father and son before. Of course, in my Christian upbringing, much was said about the word, how Jesus encouraged his disciples to call God Abba. But I have never heard it like this. I have never heard a young boy say it, his face so close to his father’s that they must be breathing the same air. His eyes pleading. His father smiling and kissing his cheeks and still saying no, but in such a loving way.

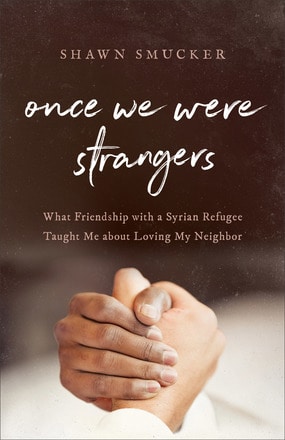

Yes, that is the kind of Daddy we are talking to when we pray. He’s holding us close, smiling, and kissing our cheeks. Our God is like this Syrian refugee, depicted in Shawn Smucker’s new book, Once We Were Strangers: What Friendship with a Syrian Refugee Taught Me about Loving My Neighbor.

Once We Were Strangers invites us into the intimacy and longing of family and friendship, our universal ache to be safe and known.

Once We Were Strangers invites us into the intimacy and longing of family and friendship, our universal ache to be safe and known. That’s not what I expected when I started the book, though. I feared it would be another hysteria piece about the dire refugee crisis, the dire political shift away from courageous compassion, and the dire outlook on Middle East–US relations.

I should have known better. Shawn’s novel, The Day the Angels Fell, was named “Book of the Year” by both Christianity Today and my family’s last Christmas letter. I read a chapter each night to my nine-year-old daughter, captivated by Shawn’s suspenseful story about friendship, death, and a mysterious tree.

I now wish all advocacy books were written by novelists. The statistics, timelines, checklists, and relevant world events aren’t weaponized; instead they are woven into a masterful story arc, filled with likable characters, epic and daily battles, and global and personal questions. Once We Were Strangers drew me in, grabbed my heart, and led me toward hope. It exceeded my expectations.

Shawn set off to write this book because he wanted to help. But in the narrative, we see his uncertainty:

“I just want to help,” I say. I don’t know what else to do. I think briefly about those words, that sentiment. Would writing a book, would getting this man’s story bound and published and sold, help? How? Who?”

Shawn admits that he initially pitched the book with exciting, Jack Ryan kinds of elements, and many of these things did happen to Mohammad and his family: his town was repeatedly bombed, his friends died, his family of six escaped by hanging on to a motorcycle, they walked hours through the desert to escape over the border, they landed in a Jordanian refugee camp, and they paid smugglers to get them out of the camp only to idle in a Jordanian apartment, forbidden to drive, work, or go to school.

Shawn could have chosen to make this book “based on a true story,” and thrown in some grenades, suicides, sexual violence, and familiar orange life vests, but that’s not a part of this true story.

In this story, Mohammad and his family struggle to begin a new life outside Syria for four years. He goes to the UN office in Jordan every week, asking how to legally get out and start a new life. There are no answers. No progress. Until suddenly there is, and after 18 months (in what I imagine would be a very non-Jack Ryan montage of endless interviews and stacks of paper) he signs a promissory note to pay the US government back for their travel expenses, boards a plane with his family, lands at LaGuardia, is greeted at the airport, and driven to Lancaster, Pennsylvania to begin again. The next day the family wakes up from their jetlag and goes for a walk to a nearby park:

The boys ran ahead. Their footsteps made soft, rhythmic sounds on the cement sidewalk, and for the first time, he was not afraid for them. They darted off toward the park once it came into view, and he did not call them back.

He realized they were safe. Finally safe. His family could grow here. In Jordan, they had stayed inside as much as possible where they were living, and their houses and apartments had become a prison to them. In Lancaster, he finally felt, for the first time in many years, that his family would be okay. They had a future now, a path laid out in front of them.

A few months later Mohammad and Shawn meet at the offices of Church World Services. Shawn sets realistic expectations about working on a book, and how “nothing” might come of their time together:

There is a kind of softness in his eyes, as if he has seen so much that he’s given up on holding grudges or clutching his anger. His shoulders have a bent-but-not-broken arch, and I see a childlike eagerness to make new friends. I wonder where he acquired his optimism. I wonder how someone 6,000 miles from home can hold so tightly to hope.

Throughout the story Mohammad is kind, friendly, open-hearted, encouraging, and hospitable. It’s not the kind of stereotypical Middle Eastern man we see in a Jack Ryan scene, all flattery and sweeping arm motions meant to lure and deceive. Mohammad pays all his bills and proudly hangs the certificate he received from Church World Services for achieving self-sufficiency in less than six months. But he needs dental work, he needs his wife to pass her drivers’ test, and he needs the schoolbus to come pick up his son. More than anything, he needs a friend.

Don’t we all?

My family moved from Chicago to Atlanta a few years ago. We moved from one job to another. We moved from one set of doctors and dentists and therapists to another. We moved from one neighborhood with smooth roads and good schools to another. We were set up for success in our new hometown, but it still has been hard. My phone bill shows that my heart still beats 765 miles north.

I recently learned that a house will be going up for sale on my best friend’s street in Illinois. Every day, I think about what it would be like to move back. To give each other our keys again. To share snowblowers and roasting pans. To know that my kids can pop over to her house if the bus comes and I’m late. To walk over and have cups of coffee in our pajamas. Recently, my friend and I let each other daydream about it out loud, and we couldn’t stop smiling into our phones. It reminded me of Mohammad, daydreaming with Shawn on the way to the dentist:

“I told [my wife] Moradi, if we live out here close to you, we can meet every day, morning and evening.” He chuckles. “Look, Shawn, look! Look at those two houses. Side by side. Like that. We can sit outside and drink coffee. We can play. The children can play.”

Mohammad and I want the same things. Far from family, far from home, we both want to live next to a friend and weave our lives together, drinking coffee and watching the kids ride bikes. That’s the kind of peace we’re both looking for.

When I finished Once We Were Strangers I immediately ordered three more copies to give as gifts. Not to give to people I suspect wouldn’t welcome refugees, in an attempt to persuade or convert them, but to give to friends who have shared the deep ache for belonging and rejoice when others have found it, too.

I continue to pray for harmony in the Middle East, for unity in my own country, and for new, unexpected friendships for my family. But this week when I pray, I will pray like my pastor suggested, remembering God is like a tender, patient, resettled refugee who delights to hear his precious child’s request.

“…we have been set free to experience our rightful heritage. You can tell for sure that you are now fully adopted as his own children because God sent the Spirit of his Son into our lives crying out, “Papa! Father!” Doesn’t that privilege of intimate conversation with God make it plain that you are not a slave, but a child? And if you are a child, you’re also an heir, with complete access to the inheritance.”

~ Galatians 4:5-7 (MSG)

Aimee Fritz delights in telling long, true stories about compassion, souls, and big mistakes, hoping to help families become lovable and loving World Changers. She’s currently writing the Family Toolkit for Kent Annan’s forthcoming book, You Welcomed Me: Loving Refugees and Immigrants Because God First Loved Us. She previously wrote the Family Toolkit for Annan’s Slow Kingdom Coming: Practices for Doing Justice. Loving Mercy, and Walking Humbly in the World.

Aimee Fritz delights in telling long, true stories about compassion, souls, and big mistakes, hoping to help families become lovable and loving World Changers. She’s currently writing the Family Toolkit for Kent Annan’s forthcoming book, You Welcomed Me: Loving Refugees and Immigrants Because God First Loved Us. She previously wrote the Family Toolkit for Annan’s Slow Kingdom Coming: Practices for Doing Justice. Loving Mercy, and Walking Humbly in the World.