Every year from December 16 to 24, Las Posadas begin in many Latin American countries and immigrant communities in the U.S. Roughly translated, posadas means “inn” or “shelter.” Las Posadas recalls the events in Luke’s Gospel leading up to Jesus’ birth. It’s a Catholic Christian observance with a sung liturgy that’s performed on the streets rather than in church.

Las Posadas is a Catholic Christian observance with a sung liturgy that’s performed on the streets rather than in church.

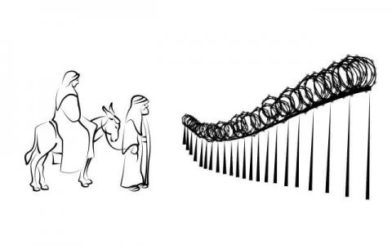

A posada begins with a street procession that reenacts Mary and Joseph’s search for shelter at an inn. Those playing the protagonists of the story, Mary and Joseph, are dressed in costume and carry candles as they follow along a prescribed route, knocking on doors. At each door they ask, through special posada songs, for room at the inn. In rural areas, Mary may even ride on a donkey.

The verses of the song are sung alternately by those outside and those inside the home. This creates a sung dialogue between Joseph and an innkeeper.

Joseph:

En el nombre del cielo (In the name of heaven)

os pido posada (I ask you for shelter)

pues no puede andar (for my beloved wife)

mi esposa amada. (can go no farther.)

Innkeeper:

Aquí no es mesón (This is not an inn)

sigan adelante (Get on with you)

yo no puedo abrir (I cannot open the door)

no sea algún tunante. (you might be a rogue.)

Many people from the community follow behind, singing along with them. The neighbors participating in the posada open their doors, and each one purposefully sings their refusal to Mary and Joseph. Only at the very end of the route is there a designated household that finally allows Mary and Joseph to come in. There, too, is a party with Bible readings, food, and piñatas for the children. Now that the holy family has found their welcome, it is time to celebrate.

Las Posadas is a beautiful Advent tradition, and a beloved part of Christmas celebrations in many Latinx communities. It is also one that ministers and immigration advocates have begun to use to represent the lack of hospitality at the U.S./Mexico border. Their version is called La Posada Sin Fronteras: Shelter without Borders.

La Posada Sin Fronteras uses the exact same songs as the traditional Posada liturgy. But rather than walking through a neighborhood and knocking on doors, immigration advocates, faith leaders, immigrants, and other supporters gather on both sides of the U.S./Mexico border. There they are watched carefully by the Border Patrol as they begin their reenactment of the journey of Mary and Joseph. The group on the Mexican side represents Mary and Joseph asking for shelter, while those on the U.S. side play the innkeeper, who repeatedly rejects their request for shelter. It’s a reenactment that “contextualizes the bitter drama” of displaced immigrants, writes Ched Myers in Our God Is Undocumented. And it brings participants inside the sacred story of God struggling to enter an inhospitable world.

Joseph (those on the Mexican side of the border wall, representing immigrants):

No seas inhumano (Don’t be inhuman)

tennos caridad (have mercy on us)

que el Dios de los cielos (God in heaven)

te lo premiará. (will reward you.)

Innkeeper (those on the U.S. side of the wall, representing the U.S. Border Patrol and, by extension, U.S. citizens):

Ya se pueden ir (You can go now)

y no molestar (and don’t bother me)

porque si me enfado (because if I become angry)

los voy a apalear. (I’m going to beat you up.)

This uncomfortable liturgy, set in a location where so much violence takes place, removes the sanitized romanticism of modern-day Christmas observances. It recalls the stark realities faced by Mary and Joseph on that night long ago. Most of us like to imagine that we would have welcomed Mary and Joseph into our homes and provided shelter. But La Posada Sin Fronteras reminds us of all the obstacles that stand in a migrant’s path and that are supported by our tax dollars: the wall at the border, the drones, the guardhouses, the tear gas, and the vigilant and heavily armed border patrol. Remembering these things keeps us firmly rooted in reality: that we likely would not have welcomed them. That in the liturgy, we are the hard-hearted innkeeper who threatens Joseph with assault.

This uncomfortable liturgy, set in a location where so much violence takes place, removes the sanitized romanticism of modern-day Christmas observances…in the liturgy, we are the hard-hearted innkeeper who threatens Joseph with assault.

I’ve never visited the Middle East, but I imagine that its climate is not unlike the one in the border city of Nogales, Arizona, which is one of the many locations where La Posada Sin Fronteras takes place. It’s not difficult to imagine Mary and Joseph trudging along the dusty, dry wilderness of Nogales where the border wall stretches for what seems like an eternity. There the holy parents plod along, seeking safety from the dictator who threatens the life of their son. There, we imagine, they know that their God sees them, and they pray someone will have mercy on them in their desperate situation.

Of course, their story in the Posada liturgy has a joyful ending. The innkeeper eventually has a change of heart. He finally recognizes Joseph and opens his door to welcome them inside:

Entren santos peregrinos, peregrinos (Enter holy pilgrims, pilgrims)

reciban este rincón (receive this corner)

no de esta pobre morada (not this poor dwelling)

sino de mi corazón. (but my heart.)

Esta noche es de alegría (Tonight is for joy)

de gusto y de regocijo (for gladness and rejoicing)

porque hospedaremos aquí (for tonight we will give lodging)

a la Madre de Dios Hijo. (to the Mother of God the Son of God.)

Those who participate in La Posada Sin Fronteras know that our story has no such happy ending—so far, at least. The wall remains. A militarized border remains. The door remains closed. There is no innkeeper having a sudden epiphany that it is the mother of God herself to whom he denies hospitality. But Las Posada Sin Fronteras are re-enacted each year as an act of faith and hope. It requires hope to act out a story with a happy ending when the story we are living doesn’t yet have such an ending—the participants are trusting that God is at work even in things they don’t see or understand. Their hopes echo the book of Hebrews which puts it this way: “Faith is the reality of what we hope for, the proof of what we don’t see” (Hebrews 11:1).

Let’s commit to bring down the wall in our lifetimes and never to internalize its divisive and inhuman message in our hearts.

Karen González is a teacher, baseball lover, and an amateur theologian in Baltimore, M.D. She works in church engagement for immigrant advocacy for a non-profit. This article is adapted from her forthcoming book, The God Who Sees: Immigrants, the Bible, and the Journey to Belong (Herald Press, 2019) and first appeared on Sojourners. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

is a teacher, baseball lover, and an amateur theologian in Baltimore, M.D. She works in church engagement for immigrant advocacy for a non-profit. This article is adapted from her forthcoming book, The God Who Sees: Immigrants, the Bible, and the Journey to Belong (Herald Press, 2019) and first appeared on Sojourners. All rights reserved. Used with permission.