In 2008, I felt like an American for the first time because I saw a leader who looked like me. All of my life I hoped my education and accomplishments would free me from the history of my skin color as inherently inferior and forever intimidating. It never did. But then Barack Hussein Obama became president of the United States, and I believed that I belonged here.

I watched his inauguration, and with each phrase I felt more optimistic. I thought, Now things are going to be different. One word defined Obama’s campaign and resonated in communities around the country.

Hope.

It was on posters, buttons, and bumper stickers in all fifty states. Somehow, saying it over and over made it feel more possible. Hope seemed not like the perfect campaign strategy but something genuine and necessary. It sounded a lot better than mounting body counts in US prisons and soldiers not returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. Especially for me—a black male graduate of Columbia University, unsure of my own ethnic identity, my place in this country, and my place in American Christianity.

I ask you to resist judgment, the urge to look away, and the opportunity to move on. I invite you to carry your skepticism through this entire book while leaning in to understand. Hold your gaze on the picture I am painting and consider its implications for how you think, speak, pray, and act. Your salvation is at stake, and your evangelism is compromised if you claim to be a follower of Jesus while building dividing walls of hostility and allowing them to govern your life. We are to be his witnesses, living differently in this world so we point others to him, and we cannot do that if we are not willing to engage with our differences to seek his justice and reflect his kingdom. I once lived this way, but because of Christ and for the sake of his gospel, I do so no longer.

…your evangelism is compromised if you claim to be a follower of Jesus while building dividing walls of hostility and allowing them to govern your life.

Lincoln, Reagan, and Obama claimed that the United States of America is the last, best hope for the world. As a follower of the Jesus of Scripture, this should have immediately drawn resistance from me. But it didn’t because being a part of something bigger felt good. I can’t see God, but I can see this opportunity and seize it. To believe that I, a black, poor, and racially profiled man, could be a part of the hope for kids in Yemen, Somalia, and Honduras felt empowering. I felt important, included, and useful. I thought my life could matter. I believed my black life did matter. A shift was happening internally as I perceived things to be changing around me. Perhaps, now with a black president of the United States I could be taken seriously, given the benefit of the doubt, and assumptions of fear and intimidation and anger toward me would lessen. I started to function as though the following were true about me too:

“We are the people we’ve been waiting for.”

“Be the change you want to see in the world.”

These quotes, from Obama and Gandhi, respectively, started to take over barbershop walls, waiting room coffee tables, and store windows.

It felt good to be an integral part of the movement to make this country a better place. Not only could I belong to this country, but I could contribute to and even lead its transformation. That is not the narrative I grew up hearing. It’s the narrative I heard of white people, both here and abroad. The only place I felt valuable was in black churches. Gospel music and black preaching weren’t theater, performance, or entertainment, but just us being us before the Lord. And now we, the ball dunkers, fast runners, and singers could also be legitimate leaders and integral contributors to the future of this country, not just slaves, labor, or entertainment.

But then the American = white = male = Christian forcefully reasserts itself.

I urge you to acknowledge the tension you might feel but not judge or disengage. With your skepticism and questions fully present, would you hold them and continue onward with a heart tuned to understand? There is a deep need for peacemakers in this world, and we can only mend to the measure that we are willing to engage with what’s broken.

There is a deep need for peacemakers in this world, and we can only mend to the measure that we are willing to engage with what’s broken.

The deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Walter Scott, and the ever-growing list of African Americans now memorialized at the hands of law enforcement eroded any hope that formed in me. This realization continued for me as I came to understand that this wasn’t just a problem for my immediate ethnic community but those I previously had not considered because of the blindness that the plight of my own people induces. Native peoples in America make up the highest percentage of police-involved killings, and the Latinx community suffers numbers comparable to the black community, and both experience the plight of invisibility with little to no media coverage.

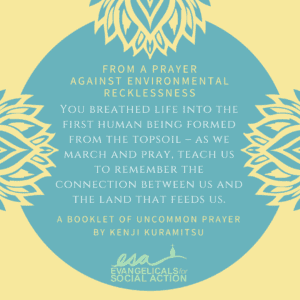

The weight of this compelled me to pray, write, march, and organize. These were all efforts to feel seen, heard, and valued in a culture that casts people of color as dangerous and disposable.

More poignantly, I remember sitting in a Sunday service on the Upper East Side of New York City the day after George Zimmerman was acquitted. The worship leader opened with a time of prayer and invited the congregation to pray aloud. Prayers for sick family members, a husband looking for a job, friends in need of healing and more people to know Jesus filled the air. I was still waiting. Waiting for anybody except me—the only black person in the room—to say “God bless the family of Trayvon Martin.” No one did. The “church” that was supposed to be my sanctuary did not see Trayvon, so this church didn’t see me, and if it did see Trayvon, his black life wasn’t worth mentioning. His black life didn’t matter, and if I met the same unjust demise, my black life wouldn’t matter either. The pastor would stand before a congregation segregated by race and class that desires to be inclusive, but when prayers are invited, no prayers would be offered for marginalized communities not in the room.

When Terence Crutcher was killed in Tulsa, I never felt so disposable. Grief was unlocked within me, and I wept in bed beside my wife, trying to make sense of a country that did not want me. America’s systems of oppression of the poor and people of color were illuminated again by police murder. This, coupled with unparalleled protection and empowerment of those with privilege and power, left me depressed and in a daze.

I had to confess this is the country and the American church I’m a part of. The community that I long to belong to doesn’t look like this. And I shouldn’t just be aware of that and know my place. I should be afraid.

In 2015, the Guardian reported that 1,146 people were killed by US police. And that number is only an estimate because it is still not mandatory to report these deaths to the Justice Department, FBI, or any other government agency. And despite being 5 percent of the population of the United States, African American males make up 15 percent of these deaths. These statistics only added to my feelings of disposability. Men and women who look like me, my momma, and my small group Bible study could end up as hashtags simply for fitting the description.

Most excruciating is the disregard for the pain and suffering that those with “the privilege of moving on” exhibit on a regular basis in the church. I should not have to convince a pastor that police brutality is a gospel issue. My fear should not be dismissed or need substantiation. The conscious and unconscious fear of people of color needs to be dealt with, not swept away. Yet with every meeting, email, and Facebook debate with my supposed brothers and sisters in Christ, I felt less and less like family and more like a stray who was allowed to be around but to never belong. I was in someone else’s Father’s house.

Prayer requests, sermons, podcasts, seminars, discipleship tools, and other components of American Christianity enmeshed with mainstream white American culture remain largely unchanged amid rapid socioeconomic and political polarization. Some of America’s most famous “Christian” leaders and institutions doubled down on bigotry, homophobia, racism, and Islamophobia. These leaders reinforced their defense of gun lobbyists, silence on sexual assault, and endorsement of greed and militarism throughout the 2016 election cycle. This reality isn’t just ideological but has real-life implications as 81 percent of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump while 88 percent of African Americans voted against him. To claim that the American church does not embody and enforce the ethnic, social, and political division and call it “Christian” is to live in denial. And to stop reading here because you disagree is cowardice.

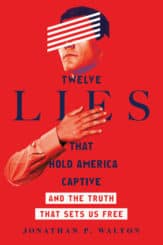

Jonathan P. Walton is an area ministry director for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship’s New York/New Jersey region. He previously served for ten years as director of the New York City Urban Project. He writes regularly for Huffington Post, medium.com, and is the author of three books of poetry and short stories. Jonathan’s work fighting human trafficking has been featured in the Christian Post, New York Daily News, and King Kulture. He has been named one of Christianity Today’s “33 Under 33,” won a Young Christian Leaders World Changer award, and was honored as one of New York’s New Abolitionists. He is a member of New Life Fellowship and lives with his wife, daughter, and dog in New York City.

Jonathan P. Walton is an area ministry director for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship’s New York/New Jersey region. He previously served for ten years as director of the New York City Urban Project. He writes regularly for Huffington Post, medium.com, and is the author of three books of poetry and short stories. Jonathan’s work fighting human trafficking has been featured in the Christian Post, New York Daily News, and King Kulture. He has been named one of Christianity Today’s “33 Under 33,” won a Young Christian Leaders World Changer award, and was honored as one of New York’s New Abolitionists. He is a member of New Life Fellowship and lives with his wife, daughter, and dog in New York City.

Adapted from Twelve Lies That Hold America Captive by Jonathan Walton. Copyright (c) 2019 by Jonathan Walton. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL.