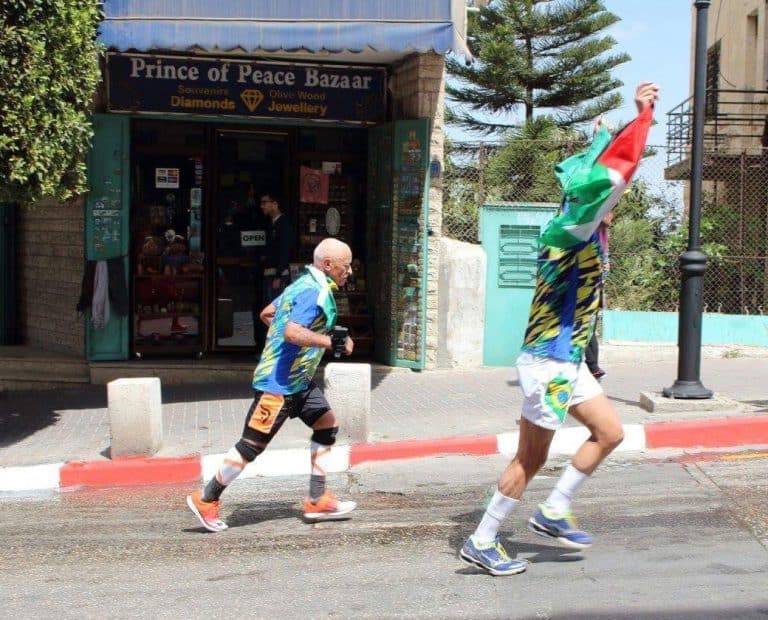

On March 23, I had the opportunity to join over 7,000 runners of all ages gathered in Bethlehem’s Manger Square, awaiting the signal to cross the starting line to begin the 6th annual Palestine Marathon. Established in support of Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that “Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each State,” the route of the Palestine Marathon begins in front of the Church of the Nativity and runs through two refugee camps. In order to demonstrate the restrictions on freedom of movement within the West Bank for Palestinians in their daily lives, runners journey alongside the eight-meter-high separation barrier and around the guard towers posted in various parts of the wall’s route.

The Palestine Marathon is a unique race, in that most participants carry a personal motive for running, tied to their view of human rights and their fundamental right to movement within their homeland. “I’m running for the freedom of my people, the Palestinians,” says Jack Sara, the President of Bethlehem Bible College. “I’m praying that the Lord will give mercies upon this land.” For Palestinians, the land of Palestine represents their history and collective identity as a people, and this race is an opportunity to physically express this intimate connection to the land and their right within this space to live out their own narratives and have freedom of movement. It is a collective voice expressing the need for change within a system that does not recognize their basic rights.

As a runner who has had the opportunity to participate in this race for the past three years, the general motivation comes from the view that the race is an opportunity to demonstrate an inherent need for change within the system of forced separation between Israelis and Palestinians. This is most clearly seen in the lack of freedom of movement, which is encountered on a daily basis by Palestinians in the West Bank. Whether traveling by foot or commuting from Bethlehem in the West Bank to Jerusalem, Palestinians face separation barriers: pop-up checkpoints and sporadic road closures, checkpoints to cross from the West Bank into Israel proper, and settler-only roads across the West Bank, on which Palestinians are forbidden from driving.

Whether traveling by foot or commuting from Bethlehem in the West Bank to Jerusalem, Palestinians face separation barriers: pop-up checkpoints and sporadic road closures, checkpoints to cross from the West Bank into Israel proper, and settler-only roads across the West Bank, on which Palestinians are forbidden from driving.

“I’m running for freedom of movement,” said one runner from the city of Tubas in the northern West Bank. “We need to breathe, we need to fly, we need to swim…[these] barriers are no longer accepted. The international community should pay attention.” One family pushing two strollers on the race course said they were running for freedom, and for their children. Many runners viewed the race itself as a physical form of expression of their need for free movement and their basic human rights, and the race was a way for participants to collectively demonstrate this by running, walking, or in some cases, dancing their way through the course.

The message of the race has annually drawn a number of international participants as well, who have traveled from throughout Europe and the United States to run in solidarity alongside the local community in a unified act of civil resistance. Participants carried flags from Finland, Ukraine, Denmark, Ireland, the UK, and other countries as a message of international recognition of the Palestinian struggle for equality. One runner from Norway was participating in his third Palestine Marathon, saying that he brings a group every year to experience the beauty of Palestine and to meet the people.

As an American Christian, this race holds significance for me as a way to encounter the city of Jesus’ birth in a way that lives out his work of redemption for the land and its people. When I reflect on Jesus’ words from the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5, and the justice that Jesus calls his disciples to yearn for through showing mercy and seeking to be peacemakers, I find the simple act of running as a way of connecting with this message of reconciliation and sending a resounding “NO” to the injustice in the land. It is a way of being part of a larger story of peacemaking, which we can all find our role within, both as individuals and as part of organizations.

As an American Christian, this race holds significance for me as a way to encounter the city of Jesus’ birth in a way that lives out his work of redemption for the land and its people.

A number of international NGO workers based in the West Bank and Jerusalem also participated in the run, including a team from UNICEF. “We’re here today with our own children to run for children in the State of Palestine,” said Genevieve Boutin, the Special Representative to the State of Palestine from UNICEF. “For children and young people still developing, the physical and mental benefits of sport and play set the foundation for healthy development and lifelong learning. It also gives them an opportunity to express themselves in a positive setting.”

Canon David Longe, the Chaplain to the Anglican Archbishop of Jerusalem, said he was running to raise funds for cancer treatment in Gaza, where the Anglican church runs the Al Ahli Arab Hospital, but lacks the resources to treat cancer patients there. Despite obstacles of cost and the blockade on Gaza, their goal is to build a cancer unit in the hospital to ensure patients in need of life-saving treatment have proper access to the medical care they need.

American runner Celia Riley has participated in the race every year since it began in 2013. She runs in solidarity with the local community in Bethlehem, and describes the race as a journey for her: “Combining my heart for justice and running, hours side-by-side with people from all over the world, experiencing the Palestinian community around us, we become witnesses to their hospitality but we also see the humanity that’s restricted by the walls and checkpoints.”

Being present in the story of this race is a contribution to a much larger narrative. It is a narrative of the collective right to movement, the firm belief that peace can prevail in the Holy Land, and that God is in the midst of this place and continuing the work of redemption here. This redemption took place as each runner ran alongside the immense separation wall and crossed the finish line, and as they retold the story of overcoming adversity to run a challenging course on a very hot day to be part of a collective story of community. Being part of this shared story recognizes the shared belief that we are contributing not only to changing the present conditions, but working towards a future in which the huge physical wall we faced together will one day come down and that future generations will be part of a shared narrative of redemption and reconciliation that was written for them, beginning with crossing the finish line of this race.

Returning for the past three years to participate in this shared journey is an honor and story I will keep telling. It is a reminder that each of us has a role in dismantling the physical, emotional, and political walls we face in our own lives and collective narratives, and that it is our sacred duty to recognize these walls within ourselves and stand in solidarity alongside those who face these walls and help tear them down.

Jesus,

I thank you for showing us your heart for justice through your everyday pursuit of peacemaking. I thank you that your Spirit continues to live among your people in the Holy Land through the work of engaging in dialogue and participating in acts of creative civil resistance. May your message of reconciliation continue to be heard, and may it spread among the Israelis and Palestinians there, so each person recognizes their role within a shared narrative of redemption of the land. And may we all support this peacemaking through our own everyday acts of peacemaking.

Amen.

Sara Burback served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Kazakhstan as an English teacher. Her experience there led her to the University of Denver’s Korbel School of International Studies, where she earned her MA in International Human Rights and served as an intern in World Vision’s Advocacy office, where she focused on addressing advocacy work within the faith-based community regarding Israel and Palestine. She recently worked as a Program Coordinator at the United States Energy Association in Washington, DC, creating workshops and exchanges addressing capacity-building and energy access needs in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. She’s served as a volunteer with CMEP for the And Still We Rise Summit, is a regular contributor to the online periodical Shared Justice, and participates annually in Bethlehem’s Right to Movement marathon in defense of the basic human right to movement.

Interested in joining a team running in the 2019 Palestine Marathon, and exploring how everyday peacemaking is embodied in Israel and Palestine? Please e-mail Churches for Middle East Peace for more information!