We are called by God to be good stewards of the earth. Unfortunately, racism gets in the way. Environmental racism, defined as the link between the degradation of the environment and the racial composition of the areas where degradation takes place, is all too prevalent among communities of color in the US. According to the 2014 study Injustice and Inequality: Outdoor NO2 Air Pollution in the United States, a correlation exists between ethnicity and the counties with the most unhealthy air quality.

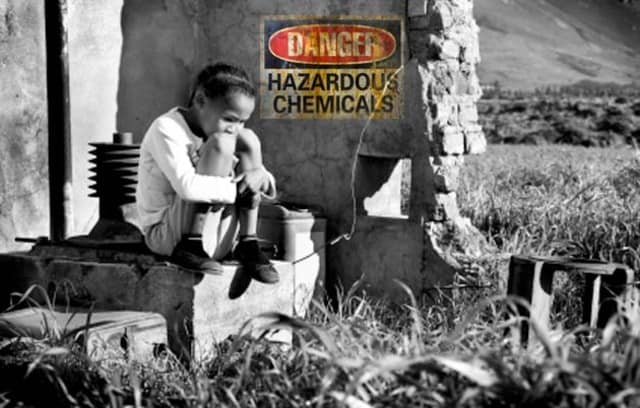

According to a growing body of empirical evidence, race continues to be the most significant variable in determining the location of commercial, industrial, and military hazardous waste sites. It is the most significant predictor in forecasting where the nation’s commercial hazardous waste facilities are located.

US Census data from 2000 show that people of color represent 56 percent of the population that lives less than 1.8 miles from one of the nation’s 413 commercial waste facilities. This means that of the 9 million Americans living in neighborhoods hosting one of these commercial hazardous waste facilities, more than 5.1 million are persons of color—2.5 million Hispanics, 1.8 million African Americans, 616,000 Asians, and 62,000 Native Americans. The poorer the community, the greater the risk of environmental abuse, because the economically privileged are able to move away from such sites, a privilege not available to the poor, who are mostly people of color.

Out of the 149 metropolitan areas with hazardous waste sites, 105 are predominately comprised of people of color. African American neighborhoods are host to such facilities within 38 of the 44 states that have them; Hispanic neighborhoods host them within 35 states; and Asian neighborhoods are hosts within 27 states.

Out of 149 metropolitan areas with hazardous waste sites, 105 are predominately comprised of people of color.

Between 1999 and 2009, the National Academy of Science produced five environmental justice reports showing that “low-income and people-of-color communities are exposed to higher levels of pollution than the rest of the nation, and that these same populations experience certain diseases in greater number than more affluent white communities.” African American ethicist Emilie Townes has said that the effects of toxic waste on the lives of people of color who are relegated to live on ecologically hazardous lands are akin to a contemporary version of lynching an entire people.

Environmental racism is not limited to hazardous waste sites. Violators of pollution laws received less stringent punishments when violations occurred in non-white neighborhoods than when they occurred in white neighborhoods. Fines were often 500 percent higher in white communities than in marginalized communities. When violations occurred in minority communities, the government was slower to act, taking as much as 20 percent more time, than when violations occurred in white communities. And even when a lawsuit (RISE v. Kay) was brought before the Eastern District Federal Court of Virginia about the placement of landfills in predominantly African American King and Queen counties, the US judge acknowledged the historical trend of disproportionately placing landfills in African American areas but still ruled that the case failed to prove discrimination.

Environmental racism also takes a heavy toll among children of color. According to a US Department of Health and Human Services study released in 2011, approximately 23 percent of poor children suffering from asthma were Puerto Rican, 21 percent multiracial, 16 percent African American, and 10 percent white.

The predominantly African American neighborhood of Central Harlem in New York City has the highest percentage of documented cases of asthma in the entire country. The worst asthma triggers are found in abundance there, specifically insect (cockroach) droppings, mold, mildew, diesel exhaust, and cigarette smoke. African American children in other areas are also vulnerable to asthma, because 68 percent live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant.

Nationwide, African American children have a 500 percent higher death rate from asthma when compared to white children. Additionally, they have a 260 percent higher emergency rate and a 250 percent higher hospitalization rate.

How should people who love justice respond to people like Senator Jefferson Beauregard Sessions (R-AL), who claimed during a Senate hearing on the EPA budget that air pollution victims are “unidentified and imaginary”? How can we help justice roll in the face of such blatant disregard for human health, equality, and dignity?

The Rev. Dr. Miguel De La Torre is a Cuban-born professor of social ethics and Latinx studies at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado. A scholar-activist, he has served as president of the Society for Christian Ethics and is the author or several books, including the revised and expanded Doing Christian Ethics from the Margins.

One Response

Non white people struggle more because they are poor and therefore do not have the ability to move or political clot to receive justice. If one examines poverty in the US one finds 17 mil white non his. Poor vs 9 mil. Black american poor. There are more Hispanics living in poverty than Blacks in numbers of people. The article in referring to poverty does not give an adequate reason why it is the Black poor though smaller in numbet suffer so.