Ron Sider is the rare evangelical Christian who takes both Scripture and social science seriously.

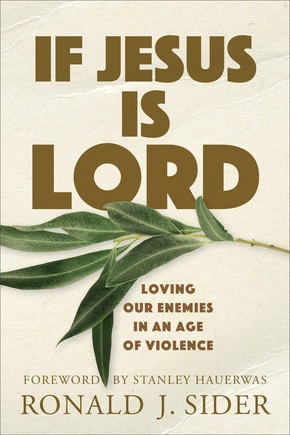

“Did Jesus mean to teach his disciples never to kill?” This question—or, if we want to frame it in the present tense, “Does Jesus ever want his followers to kill?”—forms the crux of Ron Sider’s new book on violence and faith. In If Jesus Is Lord: Loving Our Enemies in An Age of Violence, Sider critiques just war theory (which argues that violence can be deployed in pursuit of a greater good) and answers those who would accuse Christian pacifists of being “naive, simplistic, utopian,” or even “immoral” in the face of evil.

Sider has spent his career as an academic and Christian leader at the intersection of injustice and nonviolence. His seminal work Rich Christians in an age of Hunger stirred the consciences of hundreds of thousands of western Christians. His address to the Mennonite World Conference gathering in 1984 is widely credited as the catalyst for Christian Peacemaker Teams, an organization that sends volunteers to conflict zones to intervene and interrupt violence. Now approaching his retirement years, Sider has penned one more reflection on the question of whether violence can ever be justified by followers of Jesus.

In short, Sider’s answer is a resounding never. If Christians affirm Jesus as Lord, our allegiance to him means rejecting the use of lethal force. This claim is far from a novel interpretation of Christian faith. While it certainly stands at odds with much of Christian practice after Constantine, this was the view of nearly every early church leader who spoke on the subject. Clement of Alexandria (150 – 214 CE) expressed it most succinctly: “Above all Christians are not allowed to correct by violence sinful wrongdoings.” While this can be read as a straightforward statement against capital punishment, its claim is much broader: all of the things Christians would wish to correct—injustice, oppression, subjugation, cruelty, racism, sexism, xenophobia—are themselves “sinful wrongdoings.” Although not every sin is injustice, every injustice is sin. Sin—whether personal or systemic—cannot be corrected by violence.

Sider advances this line of thinking over the course of the book. At the outset, he clarifies what he means when he speaks of violence. He is speaking of lethal force. Unlike some other pacifists, Sider accepts that in some circumstances, the use of non-lethal power or even coercion is appropriate. In rejecting the deontological ideal of “absolute non-coercion in human relationships,” Sider posits an almost utilitarian pacifism that accepts “coercion (whether psychological, physical, or economic) [as] morally appropriate as long as the intent and overall effect is the promotion of everyone’s well-being and persons are not killed.” One weakness of Sider’s argument is that he fails to define what constitutes “the promotion of everyone’s well-being” (or even clarify who ought to answer such a question).

As befits his belief that Jesus is, in fact, Lord, Sider takes the ministry of the messiah as his starting point, exploring Jesus’ gospel, his actions, and his teachings (with special emphasis on the Sermon on the Mount). From there, Sider moves to the rest of the New Testament canon’s articulation of an ethic of nonviolence before he circles back to address common objections to nonviolence that find prooftexts in a few isolated, misunderstood portions of Scripture.

After articulating the nonviolent ethic of Jesus and his earliest followers, Sider leaps into modern theological debates, finding a ready foil in Reinhold Niebuhr. In Sider’s summation, Niebuhr concluded that “Jesus’s ethic does not work in the real world. Responsible Christians should not try to live the ethic of love that Jesus taught.” Jesus’ teachings, for Niebuhr and millions of modern Christians, can be followed only in some future heavenly existence, not in actual daily life. Responding to this misconception, Sider advances a four-fold argument for what he calls the “already / not yet Kingdom,” a Kingdom in which Jesus’ teachings are to be put into daily practice.

First, Jesus himself never seems to suggest that his teachings are for a future age; he intends his followers to live this way here and now. Second, Jesus’ cross—the example par excellence of self-giving love—establishes a pattern of living for Jesus’ followers. Third, the New Testament upholds an incredibly high ethical standard in every area of life. Forth, “nonconformity” is part and parcel of Christian faithfulness, so common understandings of “efficacy” or “practicality” are not proper benchmarks for Christian living.

Following this exploration of theological debates, Sider explores practical problems with both pacifism and just war thinking. His critique of just war theory might be the strongest aspect of the book. He poses a series of provocative questions to just war proponents:

“How can one kill a person and at the same time fulfill Christ’s mandate to invite that person to accept Christ? How can one obey Christ’s command to love one’s enemies while one is killing them? Have the just war criteria actually been applied to real-life in a way that has prevented or ended war? … What should one conclude from the fact that for centuries, just war Christians have regularly fought and killed other Christians?”

From Sider’s vantage point (and mine), just war theory offers no cogent response to these objections. Since just war theory fails to comport with the New Testament witness, and since it fails to reduce violence in the world, it should be set aside in favor of Jesus’ uncompromising ethic of love.

Since just war theory fails to comport with the New Testament witness, and since it fails to reduce violence in the world, it should be set aside in favor of Jesus’ uncompromising ethic of love.

Sider is the rare Evangelical Christian who takes both Scripture and social science seriously. He revised Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger to better reflect the economic development of parts of Asia and Latin America. In If Jesus Is Lord, Sider recognizes the important work of Erica Chenoweth and Maria. J. Stephan, who studied “all the known cases of major armed and unarmed insurrections from 1900 to 2006.” Their conclusion? “Nonviolent resistance campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts.” Nonviolence works in practice, not just in theory.

Sider’s work would be strengthened, however, if he took more seriously the critical and theological reflections of those living under oppression. Sider, like me, is a white American, occupying by default a position of absurd privilege and comfort. The overwhelming majority of Sider’s sources are also white men. While he nods approvingly toward Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, and Desmond Tutu, he fails to engage seriously with their intellectual work. Also conspicuously absent are women’s voices. Where are the voices of womanist theologians like Mitzi Smith or Stacey Floyd-Thomas or practitioners of nonviolence like Leymah Gbowee? The absence of women’s perspectives is further highlighted by Sider’s reliance on the work of John Howard Yoder, whose abuse of women was nearly as prolific as his writings. To Sider’s credit, though, he acknowledges and condemns Yoder’s misconduct.

Even with these shortcomings, If Jesus Is Lord is a masterful defense of pacifism as the only faithful option for followers of Christ. As Martin Luther King, Jr. made clear, “violence cannot drive out violence.” If Christians seek a more just society, we must reject lethal force and embrace the difficult path of the cross, loving our enemies and doing good to those who hate us.

Jon Carlson serves as Lead Pastor of Forest Hills Mennonite Church outside of Lancaster, PA. Jon and his wife, Lyn, are raising three kids who seem to have endless supplies of energy. Follow him on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram.

Jon Carlson serves as Lead Pastor of Forest Hills Mennonite Church outside of Lancaster, PA. Jon and his wife, Lyn, are raising three kids who seem to have endless supplies of energy. Follow him on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram.