In many relational conflicts, an outsider does not want to venture too far into the middle. Divorce among friends is often such a conflict. So, too is the rejection of faith by the child of a prominent evangelical leader. Some of these broken relationships and ensuing tensions feel like a no-win situation. Everybody is inclined to lose.

I felt this way reading Tony and Bart Campolo’s book. There are times when you don’t want to have to choose sides. The pain of the brokenness can wash over you as well. Nonetheless, this is an instructive dialogue.

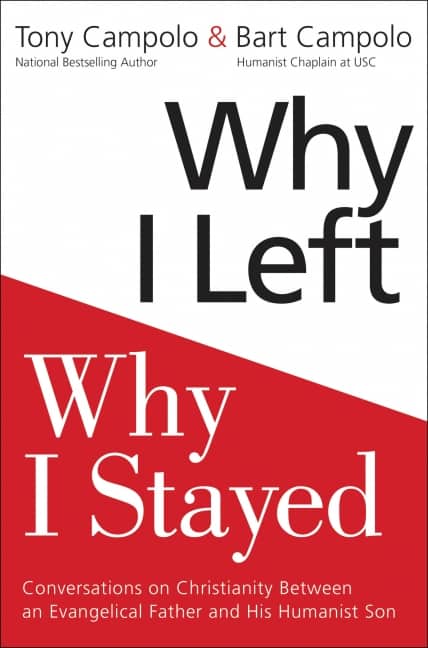

Tony and Bart Campolo’s book, Why I Left, Why I Stayed: Conversations on Christianity Between an Evangelical Father and His Humanist Son is intended to be a hopeful book showing how difficult familial conflicts can be navigated with love. Nonetheless, it was a book that made me sad. Tony is a respected colleague of mine. Bart I have never met, but I get the sense that I would like him very much. As a secular humanist he has a winsome candor and humility that sets him above most of his secular peers. Perhaps because I also grew up in the shadow of a celebrity Christian father, I can relate to his difficult journey of making spiritual commitments his own, even if we have not taken the same path.

This book highlights a reality that has been brushed under the rug in too many churches: evangelical parents are losing their children to various forms of secularism in growing numbers. The rise of the “religious nones” has received a great deal of press. Over a third of millennials, those born between 1980 and 2000, now fall into this category—religiously unaffiliated, unchurched, or agnostics and atheists. The evangelical church has an epidemic of prodigal children, and our silence about this phenomenon does nothing to equip their parents in their pain and sense of failure.

The evangelical church has an epidemic of prodigal children, and our silence about this phenomenon does nothing to equip their parents in their pain and sense of failure.

Poignantly, Peggy Campolo—wife of Tony and mother of Bart—writes the foreword to this book. She wonders aloud whether Bart’s rejection of faith in middle age was not somehow her fault. “What I deeply regret is that that day [her genuine conversion to faith in Jesus] came far too late for my children to have been raised by a truly authentic Christian mother. My son was nineteen and off at college when Jesus became a real part of my life.” Her sense of guilt is real, but it’s unfounded. All of our children have to make their parents’ faith—or lack thereof—their own. When our children turn out great, parents are quick to take credit. When they turn out poorly, not so much. But in both cases we tend to minimize our children’s self-determining agency. Parents have an influence, but they are never in control. Our children’s self-determination needs to be respected. Our children will each have to make their faith their own, and it is today, even more so than in the past, rarely a smooth, trauma-less process. We need far more forums in our churches where these issues can be discussed, where tears can be shed and the sense of guilt comforted. We have classes on good prospective parenting, but few on what many perceive to be parenting failure after the fact. The promised pain in childbirth includes childrearing (Genesis 3:16a). We need these classes. There is a lot of unnecessary guilt being held by evangelical parents.

This dialogue between Tony and Bart is meant to be a useful corrective, and is long overdue. As Tony observes, “For most of us there is no safe place to discuss the difficult issues of faith or to work through doubts and questions.” Consider this statement from famed atheist Bertrand Russell at age fourteen:

I became exceedingly religious and consequently anxious for supposing religion to be true. For the next four years a great part of my time was spent in secret meditation upon this subject. I could not speak to anybody about it for fear of giving pain. I suffered acutely, from the gradual loss of faith and from the necessity of silence.

Our corporate silence is a breeding ground for both individual skepticism and parental anguish.

The book is structured as a loose conversation, with alternating chapters written by Tony and Bart. These back and forth interactions really took place, specifically on a week-long speaking tour in England, where Tony invited Bart to be his travelling and conversation companion. The book ends with a joint conclusion where they outline lessons each learned from their ongoing painful and inconclusive exchange. I found this to be the most valuable contribution of this book.

Tony and Bart both work hard here to affirm relationally that “love is the most excellent way.” Parents do well to remember that there is no influence without a personal relationship. In the end, our relationship with our prodigal children is less about winning arguments than it is about being fully present with them in the midst of their spiritual journey—however bizarre or heretical their journey may feel. This kind of nonjudgmental presence cannot happen easily if the picture you have of faith is of a binary light switch, instead of an ongoing pilgrimage, a one-time event rather than an ongoing process. As the authors note, “We agree that it is nearly impossible for people on opposite sides of the faith divide to have a warm, constructive conversation about religion and spirituality unless and until they first resolve to leave ultimate judgments about eternal salvation in the hands of God.” It is not productive to enter into these conversations from a know-it-all perspective—whether its a Christian know-it-all or humanist know-it-all viewpoint. Faith is a journey, not a light switch; a process, not an event. Our role is to respectfully enter into the journey of the other, listen, love, and periodically ask useful questions. Modern millennials are less and less likely to respond to people trying to show them the truth and convert them. Increasingly, they will need to come to belief on their own—granted with our loving nudging. But the posture of confident assertion is no longer effective. Bart warns, “It is hard to meaningfully engage with someone who thinks of you as a ‘dead man walking.’” It is far better to think of your prodigal as a fellow hiker, conversation partner, and mutual guide on life’s spiritual Appalachian Trail.

In the end, our relationship with our prodigal children is less about winning arguments than it is about being fully present with them in the midst of their spiritual journey—however bizarre or heretical their journey may feel.

Tony and Bart also rightly point out that both parties in this conversation need “to be more interested in listening to and understanding the other person than in convincing them to change their minds.” The context needs to be one of humility and forgiveness, as well as a sense that there is much one can learn from the other. As long as one party believes that they have a corner on truth and nothing left to learn, the result is a set of alternating speeches, rather than real dialogue. One needs, ideally, to enter into the premises and perspective of the other. The secularist needs to be wooed from within a secularist perspective, not harangued from an evangelical one. A confident secularist might be open to reading and discussing the works of other thoughtful but humble secularists such as Julian Barnes’ Nothing to be Frightened Of, Peter Rollins’ The Idolatry of God, Thomas Nagel’s Mind & Cosmos, or David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. This will be a much more interesting to them—and perhaps even fruitful—than rehashing the likes of Josh McDowell or C.S. Lewis.

Finally, Tony and Bart correctly observe, “What moves people most are stories.” Frame shifts do not happen by the application of more facts or cogent arguments. As Berkeley professor George Lakoff notes, when the facts don’t fit the frame, the facts bounce off and the frame stays. The primary issue between Tony and Bart is a difference of frames—naturalist (reality is what is empirically provable via science) versus supernaturalist (reality has aspects that exist that are beyond what is empirically provable by science). Frame shifts—such as between naturalism and supernaturalism—are not possible with the application of more left-brain rational thinking. Here, especially, stories and the application of the imagination must prevail. Stories engage the whole person more than rational arguments.

Even more influential than stories is lived experience. To the casual skeptic, Francis Schaeffer would tell them to go out and live like hell for six months and come back to report on how well that worked. He always pointed out that the real existential rub is never in the argument but in the living. We need a greater application of lived experience, not philosophical abstractions. This is wise advice and it is heartening to see a father and son wrestle through the inevitable surface tensions of a loving disagreement on matters of ultimate concern. As Jesuit priest and theologian John Courtney Murray observed, “Disagreement is a rare achievement and most of what is called disagreement is simply confusion.” Genuine disagreement is an achievement, and such achievement is evidenced here. Most disagreements do not clarify the points of disagreement in a respectful manner. Rather they simply add more confusion in an escalating cycle of talking past one another. Few parents and children in similar circumstances get a far as Tony and Bart.

While these contributions are real and noted, I found the book largely unsatisfying and dated. There was a failure to address each person’s respective differences of frame. Rather, they talked about how they see things differently through their own frames. This is interesting but it is not an example of rhetorical influence or persuasion.

First, note the binary framing of the book. It is structured as an either/or conversation, as one might well expect in a dialogue between a confident evangelical and an equally confident humanist. This kind of framing precludes an awareness that reality is more complicated that black and white answers. Reality is far more both/and than either/or, far closer to ambiguity and complexity than certainty and simplicity. Quantum physics has proven this point. This binary framing is a telltale marker of the two authors’ shared modernist Enlightenment left-brain bias. What we have here is a dialogue that is the flip side of the same coin—an Enlightenment fundamentalism. Bart has flipped the script, but not the frame. He has the same kind of cognitive certainty that his father has about his position—only now he is advocating humanism. He and his father both are maintaining a closed frame. Both share their indebtedness to the Enlightenment perspective of certainty.

This kind of framing precludes an awareness that reality is more complicated that black and white answers.

It is for this reason that the book feels very dated. It could have just as easily have been written in 1880, with Bart’s heavy reliance on “The Great Agnostic” Robert Ingersoll. The entire postmodern critique of Enlightenment modernism is nowhere to be found. Tony makes this point: “What I believe Bart does not properly consider is that the kind of modern thinking championed by Ingersoll is increasingly outdated in this postmodern stage of history.” Nowhere is there Derrida, Lyotard, or Lacan—leading postmodernist critics of the Enlightenment. Likewise, the epistemic humility of these later thinkers is also absent. Both take instead a dogmatic posture towards truth and one another that is cautioned, even undermined, by these later postmodern critics. Calvin College philosopher James K.A. Smith reminds us “One of the reasons postmodernism has been the bogeyman for the Christian church is that we have become so thoroughly modern. But while postmodernism may be the enemy of our modernity, it can be an ally of our ancient heritage.” This continuing reliance on the assumptions of modernity are evident in both Tony and Bart.

So not only is the framing wrong and the arguments dated, the genuine mutual engagement of ideas is virtually nonexistent. Arguments are made from within their own frames, and consequently most of their dialogue on substance talks right past each other. What we have here is a subjective experiential evangelist engaging, from within an evangelical frame, a secular empirical humanist. What unfolds illustrates the Korean adage, “East question; West answer.” The viewpoints are philosophically incommensurate and little effort is made to work within each other’s frame or to bridge the gaps in their perspective. Instead, we have long discourses of well-intentioned talking past one another.

If arguments were to count, Bart wins hands down. He makes an argument. Tony, in contrast, tends to speak only as an evangelist, not as an apologist. Faith, for Tony, becomes simply an existential choice. He writes, “I believe in God because I decided to. Then, having made that decision, I set about constructing theories and arguments to substantiate what I already had decided to believe…. As an evangelist, I encourage people to give the Gospel a chance, knowing that if they make that decision, the Holy Spirit will bear witness with their spirits that God is quite real and that they are God’s children.” We are then reminded that John Wesley’s heart was “strangely warmed” at Aldersgate, showcasing the experiential character of evangelical belief. This is not an argument that will convince many today, much less a thoughtful, science-oriented secularist. If this is all there is to support belief in the supernatural, then I’m with Bart. Fortunately, there is more to say than is stated here about the philosophical and existential weaknesses of naturalism.

What both Tony and Bart need to consider is a more thorough-going abandonment of their Enlightenment reliance. To this end, they would be well-advised to read agnostic neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. McGilchrist argues that the West’s over-reliance on left-brain rationalism—the Enlightenment way of thinking—has trapped us in a “hall of mirrors.” Our over reliance on abstractions, a consequence of this way of thinking, makes it impossible to comprehend or connect with actual embodied reality, thus the “hall of mirrors” metaphor. Neuroscience suggests that one can’t get to a more accurate assessment of reality without a greater degree of humility, and without a change of frames that starts with right-brain intuition. The binary Enlightenment-shaped world depicted here by Tony and Bart should leave readers dissatisfied because it doesn’t do justice to the complexity and ambiguity of lived experience. In today’s world, there are fewer and fewer people who are continuing to think in this older manner. Increasingly, both kinds of fundamentalists, Christian and humanists, are increasingly passé.

The binary Enlightenment-shaped world depicted here should leave readers dissatisfied because it doesn’t do justice to the complexity and ambiguity of lived experience.

American evangelicalism’s ongoing complicity with the Enlightenment left-brain framing of reality creates a situation where, under certain circumstances, Bart’s rejection of faith for humanism is understandable. As McGilchrist warns, “The Western church has been active in undermining itself.” McGilchrist goes on to conclude, “I would also like to put in a word for uncertainty. In the field of religion there are dogmatists of no-faith [e.g. Bart] as there are of faith [e.g. Tony], and both seem to me closer to one another than those who try to keep the door open to the possibility of something beyond the customary ways in which we think, but which we would have to find, painstakingly, for ourselves.” Eastern Orthodox theologian Elder Porphyrios wisely suggests, “Whoever wants to become a Christian must first become a poet.” He is alluding to this alternative right-brain way of processing reality. This new way of thinking that points to something beyond is where many people are today finding onramps to new spiritual journeys. The dogmatic Enlightenment binaries of the Campolos should leave one unsatisfied with both. Gratefully, the inner workings of the brain and contemporary neuroscience point to another way. This is a signpost to a more promising path for spiritual seeking.

John Seel is a consultant, writer, cultural analyst, and cultural renewal entrepreneur. He is the founder of John Seel Consulting LLC, a social impact consulting firm working with people and projects that foster human flourishing and the common good. The former director of cultural engagement at the John Templeton Foundation, he is a national expert on millennials and the New Copernicans. He has an M.Div. from Covenant Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Maryland (College Park). He and his wife, Kathryn, live in Lafayette Hill, PA. He directs the New Copernican Empowerment Dialogues at The Sider Center at Eastern University.